Every two weeks since 2023, US officers convene a classified intelligence briefing about fighting in the Red Sea. The attendees aren’t politicians, policymakers or spies. They are private shipping executives. The meetings are part of a push by the Pentagon’s Transportation Command, or Transcom, to integrate shipping lines as crisis supply lines. The policy stems from a dire need in an unloved but vital corner of America’s military behemoth. A House select committee in February 2024 called Transcom’s sea-cargo capacity “woefully inadequate.” The U.S. is investing heavily in new weapons systems, but missiles, warships and jet fighters are only a fraction of what the military worries about. Troops sent to battle also need food and water. Their equipment devours fuel and spare parts. Guns without ammunition are dead weight. Wounded fighters require evacuation.

Moving all of that—and keeping supplies flowing for months or years—demands vast and complex support infrastructure, broadly termed logistics. If it doesn’t function, even a battle-proven force will grind to a halt…China’s rise has exposed America’s shipping weakness. Beijing isn’t just Washington’s biggest military rival. It is also by far the world’s biggest logistics operation. Within China’s centrally directed economy, the government controls commercial shippers, foreign port facilities and a globe-spanning cargo-data network that in a conflict could be repurposed for military aims or to undermine the U.S., including on home soil. Transcom’s fleet of planes and cargo ships, meanwhile, is aging and insufficient.

In conflict with China, the Pentagon would send roughly 90% of its provisions by sea. Among 44 government-owned ships for moving vehicles that Transcom can tap, 28 will retire within eight years. Replacements have faced repeated delays. But military logistics isn’t “just logistics” because in wartime, supply lines are prime targets. During Russia’s assault on Kyiv in 2022, Ukrainians crippled Moscow’s forces by destroying their provisions.

Robust logistics, in contrast, can deter attacks. If adversaries believe the U.S. can quickly mobilize a massive response, they are less likely to initiate hostilities. During the Cold War, North Atlantic Treaty Organization allies routinely made a show of flooding Europe with American troops and gear before exercises.

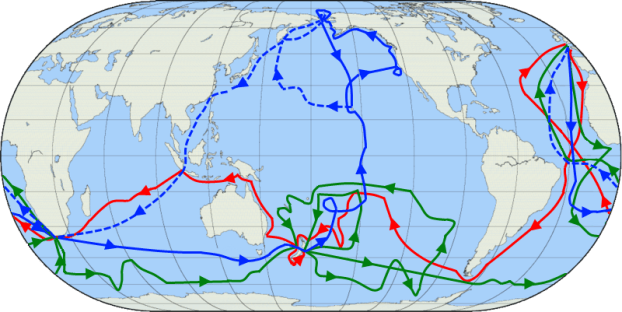

The U.S. has decades of experience working with NATO allies to send military supplies to Europe for a potential conflict with Russia. Cargo ships generally need about two weeks to cross the Atlantic. For a conflict with China, logistics would be more complicated because distances are far greater. Crossing the Pacific takes much longer than the Atlantic, and shipping routes could face greater danger of attack.

In 1990, at the Cold War’s end, the U.S. had roughly 600 available merchant ships. In 1960, it had more than 3,000. China today has more than 7,000 commercial ships. Chinese entities own every sixth commercial vessel on the seas—including ships flying other countries’ flags—a share comparable only to Greece.

Excerpts from Daniel Michaels and Nancy A. Youssef, Pentagon’s limited capacity to support a potential China conflict forces planners to tap private cargo companies, WSJ, Nov. 1, 2024