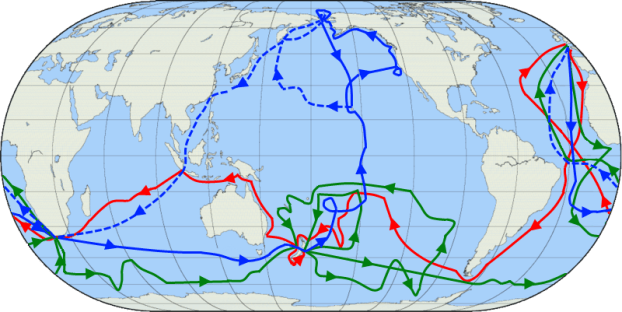

The old port of Colombo, Sri Lanka took centuries to reach its present capacity. China will have almost doubled it in under 30 months. Operated at full capacity, it would make Colombo one of the world’s 20 biggest container ports. In the eyes of some Indians, Colombo is part of a “string of pearls”—an American-coined phrase that suggests the deliberate construction of a network of Chinese built, owned or influenced ports that could threaten India. These include a facility in Gwadar and a port in Karachi (both in Pakistan); a container facility in Chittagong (Bangladesh); and ports in Myanmar.

Is this string theory convincing? Even if the policy exists, it might not work. Were China able to somehow turn ports into naval bases, it might struggle to keep control of a series of Gibraltars so far from home. And host countries have mood swings. Since Myanmar opened up in 2012, China’s influence there has decreased. China love-bombed the Seychelles and Mauritius with presidential visits in 2007 and 2009 respectively. But since then India has successfully buttered up these island states and reasserted its role in the Maldives. Besides, China’s main motive may be commerce. C. Raja Mohan, the author of “Samudra Manthan”, a book on Sino-Indian rivalry in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, argues that China’s port bases partly reflect a desire to get easier sea access for trade to and from west China.

State-owned firms are in charge of most of China’s maritime activity, and their motives are at least partly commercial…China’s maritime interests already reflect its status as the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer. Many of the world’s biggest container ports are in China. It controls a fifth of the world’s container fleet mainly through giant state-owned lines. By weight, 41% of ships built in 2012 were made in China.

The next step is to own and run ports. Hutchison Whampoa, a buccaneering, privately owned Hong Kong conglomerate, has long had a global network of ports. The pioneer among mainland firms was Cosco Pacific, an affiliate of state-owned Cosco, China’s biggest shipping line. In 2003-07 it took minority stakes in terminals in Antwerp, Suez and Singapore. In 2009 it took charge of half of Piraeus Port in Greece. It has invested about $1 billion abroad. China Merchants Holdings International, a newcomer, has spent double that. It invested in Nigeria, as well as Colombo, in 2010. Last year it took stakes in ports in Togo and Djibouti. In January it bought 49% of Terminal Link, a global portfolio of terminals run by CMA CGM, an indebted French container line.

The pace is quickening. In March another firm, China Shipping Terminal, bought a stake in a terminal in Zeebrugge in Belgium. On May 30th China Merchants struck a multi-billion deal to create a port in Tanzania. Even the more cautious Cosco Pacific is thinking about deals in South-East Asia and investing more in Greece.

China Shipping Terminal has small stakes in facilities in Seattle and Los Angeles, according to Drewry, a consultancy. But the experience of Dubai’s DP World suggests that America would not roll out a red carpet. In 2006 DP abandoned plans to buy American ports after a political backlash. Some Americans worry that China wants to take over the Panama canal.

Chinese firms may also subscribe to a supersized vision of the industry in which an elite group of ports caters to a new generation of mega-vessels. These will be more fuel-efficient and link Asia and Europe (they can just squeeze through the Suez Canal). After a decade of hype these behemoths are now afloat. In May CMA CGM received the Jules Verne, the world’s largest container ship. It can handle 16,000 containers and has a 16-metre (52-feet) draft. In July Maersk, a Danish line, will launch an 18,000-container monster. It has ordered 20 from Daewoo, in Korea. China Shipping Container Lines, the country’s second biggest firm, has just ordered five 18,400-container vessels from Hyundai. Some ports may struggle to cater to these ships. Some of China’s new terminals may try to exploit that. Cosco Pacific is building a dock at Piraeus that can handle mega-ships. Colombo is deep enough for ships with an 18-metre draft. Its cranes can cope with ships 24 containers wide. Nothing in India compares with that…

After political tensions in the South China Sea, China Merchants has withdrawn from a port project in Vietnam. But Cosco’s Piraeus investment, once controversial, is a success, with profits rising and the firm winning plaudits for investing and creating jobs for Greeks.

China’s port strategy is mainly motivated by commercial impulses. It is natural that a country of its clout has a global shipping and ports industry. But it could become a flashpoint for diplomatic tensions. That is the pessimistic view. The optimistic one is that the more it invests, the more incentive China has to rub along better with its trading partners. This, not deliberate expansionism, is what the locals are betting on in Colombo.

China’s foreign ports: The new masters and commanders, Economist, June 8, 2013