Powered by advances in artificial intelligence (AI), face-recognition systems are spreading like knotweed. Facebook, a social network, uses the technology to label people in uploaded photographs. Modern smartphones can be unlocked with it… America’s Department of Homeland Security reckons face recognition will scrutinise 97% of outbound airline passengers by 2023. Networks of face-recognition cameras are part of the police state China has built in Xinjiang, in the country’s far west. And a number of British police forces have tested the technology as a tool of mass surveillance in trials designed to spot criminals on the street. A backlash, though, is brewing.

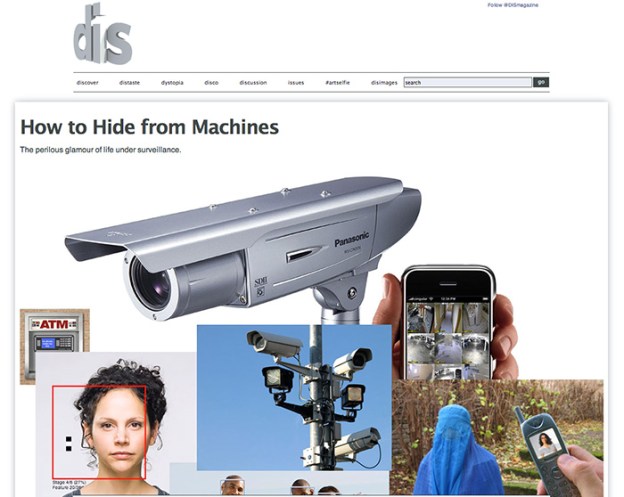

Refuseniks can also take matters into their own hands by trying to hide their faces from the cameras or, as has happened recently during protests in Hong Kong, by pointing hand-held lasers at cctv cameras. to dazzle them. Meanwhile, a small but growing group of privacy campaigners and academics are looking at ways to subvert the underlying technology directly…

In 2010… an American researcher and artist named Adam Harvey created “cv [computer vision] Dazzle”, a style of make-up designed to fool face recognisers. It uses bright colours, high contrast, graded shading and asymmetric stylings to confound an algorithm’s assumptions about what a face looks like. To a human being, the result is still clearly a face. But a computer—or, at least, the specific algorithm Mr Harvey was aiming at—is baffled….

HyperFace is a newer project of Mr Harvey’s. Where cv Dazzle aims to alter faces, HyperFace aims to hide them among dozens of fakes. It uses blocky, semi-abstract and comparatively innocent-looking patterns that are designed to appeal as strongly as possible to face classifiers. The idea is to disguise the real thing among a sea of false positives. Clothes with the pattern, which features lines and sets of dark spots vaguely reminiscent of mouths and pairs of eyes are available…

Even in China, says Mr Harvey, only a fraction of cctv cameras collect pictures sharp enough for face recognition to work. Low-tech approaches can help, too. “Even small things like wearing turtlenecks, wearing sunglasses, looking at your phone [and therefore not at the cameras]—together these have some protective effect”.

Excerpts from As face-recognition technology spreads, so do ideas for subverting it: Fooling Big Brother, Economist, Aug. 17, 2019