Tomohon, in the highlands of North Sulawesi, Indonesia is …the “extreme market”. There is certainly something extreme about the serried carcasses, blackened by blow torches to burn off the fur, the faces charred in a rictus grin. The pasar extrim speaks to Sulawesi’s striking biogeography. The Indonesian island straddles the boundary between Asiatic and Australian species—and boasts an extraordinary number of species found nowhere else. But the market also symbolises how Asia’s amazing biodiversity is under threat. Most of the species on sale in Tomohon have seen populations crash because of overhunting (habitat destruction has played a part too)…

Tomohon, in the highlands of North Sulawesi, Indonesia is …the “extreme market”. There is certainly something extreme about the serried carcasses, blackened by blow torches to burn off the fur, the faces charred in a rictus grin. The pasar extrim speaks to Sulawesi’s striking biogeography. The Indonesian island straddles the boundary between Asiatic and Australian species—and boasts an extraordinary number of species found nowhere else. But the market also symbolises how Asia’s amazing biodiversity is under threat. Most of the species on sale in Tomohon have seen populations crash because of overhunting (habitat destruction has played a part too)…

An hour’s drive from Tomohon is Bitung, terminus for ferry traffic from the Moluccan archipelago and Papua, Indonesia’s easternmost province. These regions are even richer in wildlife, especially birds. Trade in wild birds is supposedly circumscribed. Yet the ferries are crammed with them: Indonesian soldiers returning from a tour in Papua typically pack a few wild cockatoos or lories to sell. One in five urban households in Indonesia keeps birds. Bitung feeds Java’s huge bird markets. The port is also a shipment point on a bird-smuggling route to the Philippines and then to China, Taiwan, even Europe. Crooked officials enable the racket.

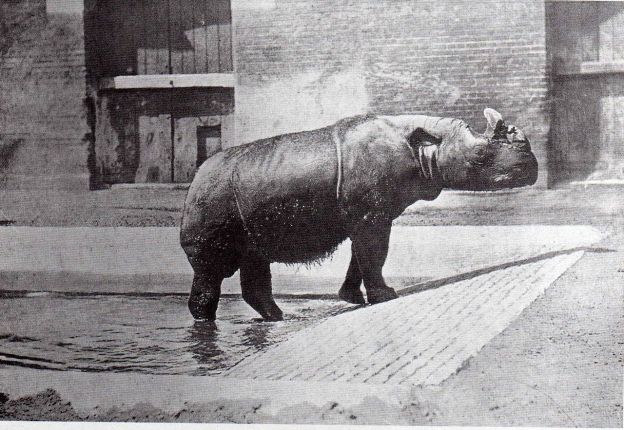

The trade in animal parts used for traditional medicine or to denote high status, especially in China and Vietnam, is an even bigger racket. Many believe ground rhino horn to be effective against fever, as well as to make you, well, horny. Javan and Sumatran rhinos were not long ago widespread across South-East Asia, but poaching has confined them to a few tiny pockets of the islands after which they are named. Numbers of the South Asian rhinoceros are healthier, yet poachers in Kaziranga national park in north-east India have killed 74 in the past three years alone.

Name your charismatic species and measure decline. Between 2010 and 2017 over 2,700 of the ivory helmets of the helmeted hornbill, a striking bird from South-East Asia, were seized, with Hong Kong a notorious transshipment hub. It is critically endangered. As for the tiger, in China and Vietnam its bones and penis feature in traditional medicine, while tiger fangs and claws are emblems of status and power. Fewer than 4,000 tigers survive in the wild. The pressure from poachers is severe, especially in India. The parts of over 1,700 tigers have been seized since 2000.

Asia’s wildlife mafias have gone global. Owing to Asian demand for horns, the number of rhinos poached in South Africa leapt from 13 in 2007 to 1,028 last year. The new frontline is South America. A jaguar’s four fangs, ten claws, pelt and genitalia sell for $20,000 in Asia…Schemes to farm animals, which some said would undercut incentives to poach, have proved equally harmful. Lion parts from South African farms are sold in Asia as a cheaper substitute for tiger, or passed off as tiger—either way, stimulating demand. The farming of tigers in China, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam provides cover for the trafficking of wild tiger parts. Meanwhile, wild animals retain their cachet—consumers of rhino horn believe the wild rhino grazes only on medicinal plants.

Excerpts from Wasting Wildlife, Economist, Apr. 21, 2018, at 36

SUDAN, the last male northern white rhinoceros on Earth, died in March 2018. He is survived by two females, Najin and her daughter Fatu, who live in a conservancy in Kenya. This pair are thus the only remaining members of the world’s most endangered subspecies of mammal. But all might not yet be lost. Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, in Berlin, in collaboration with Avantea, a biotechnology company in Cremona, Italy, is proposing heroic measures to keep the subspecies alive. In a paper published in Nature, he and his colleagues say that they have created, by in vitro fertilisation (IVF), apparently viable hybrid embryos of northern white rhinos and their cousins from the south. This, they hope, will pave the way for the creation of pure northern-white embryos.

SUDAN, the last male northern white rhinoceros on Earth, died in March 2018. He is survived by two females, Najin and her daughter Fatu, who live in a conservancy in Kenya. This pair are thus the only remaining members of the world’s most endangered subspecies of mammal. But all might not yet be lost. Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, in Berlin, in collaboration with Avantea, a biotechnology company in Cremona, Italy, is proposing heroic measures to keep the subspecies alive. In a paper published in Nature, he and his colleagues say that they have created, by in vitro fertilisation (IVF), apparently viable hybrid embryos of northern white rhinos and their cousins from the south. This, they hope, will pave the way for the creation of pure northern-white embryos.

Tomohon, in the highlands of North Sulawesi, Indonesia is …the “extreme market”. There is certainly something extreme about the serried carcasses, blackened by blow torches to burn off the fur, the faces charred in a rictus grin. The pasar extrim speaks to Sulawesi’s striking biogeography. The Indonesian island straddles the boundary between Asiatic and Australian species—and boasts an extraordinary number of species found nowhere else. But the market also symbolises how Asia’s amazing biodiversity is under threat. Most of the species on sale in Tomohon have seen populations crash because of overhunting (habitat destruction has played a part too)…

Tomohon, in the highlands of North Sulawesi, Indonesia is …the “extreme market”. There is certainly something extreme about the serried carcasses, blackened by blow torches to burn off the fur, the faces charred in a rictus grin. The pasar extrim speaks to Sulawesi’s striking biogeography. The Indonesian island straddles the boundary between Asiatic and Australian species—and boasts an extraordinary number of species found nowhere else. But the market also symbolises how Asia’s amazing biodiversity is under threat. Most of the species on sale in Tomohon have seen populations crash because of overhunting (habitat destruction has played a part too)…