Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.

Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.

That observation is of great interest to the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). DARPA’s Neurotechnology for Intelligence Analysts programme is dedicated to exploiting it in the search for things like rocket launchers and roadside bombs in drone and satellite imagery. To that end it has been paying groups of researchers to look into ways of using P300 to cut human consciousness out of the loop in such searches.

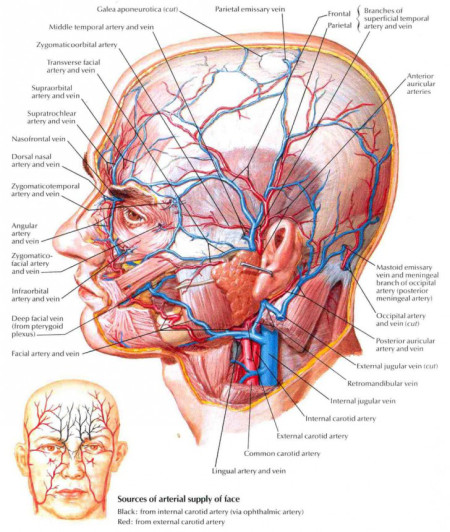

Among the beneficiaries are Robert Smith’s group at Honeywell Aerospace, in Phoenix, Arizona, and Paul Sajda’s at Neuromatters, in New York. Both of the “image triage systems” designed by these groups require the humans in them to wear special skull-enclosing caps. Each cap is fitted with 32 electrodes that record the brain’s electrical responses to whatever stimuli it is subjected to. Wearers have pictures flashed before their eyes at the rate of ten a second. That is too fast for conscious recognition, because the brain’s attention will have moved on to the next image before consciousness can come into play. It is not, though, too fast for the initial stages of recognition, marked by a P300 signal, to occur when suspicious items are present. Images that provoke such a signal are then tagged for review. According to Dr Sajda, this triples the speed with which objects of interest can be found.

Speed is important, of course. But in matters such as this, accuracy matters more. And some people think they can improve that, too—not by reading the brain, but by stimulating it. Many studies have shown that zapping the brain with a weak electric current, a procedure called transcranial neuronal stimulation, enhances what is known as “fluid intelligence”. This is the ability to reason, as opposed merely to recall facts. Another American military-research establishment, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), hopes to exploit this phenomenon for the purpose of target identification….[W]ith a current of just two milliamps, the stimulation is painless and safe, says Vincent Clark, a neuroscientist at the University of New Mexico. In a project paid for in part by IARPA, he and his team have stimulated the brains of more than 1,000 volunteers using a 9V battery connected to electrodes on the scalp. After half an hour of stimulation, volunteers spot in test photographs 13% more snipers, makeshift bombs and the like than do volunteers given a “sham” current of 100 microamps (5% of the experimental current) that mimics the skin-tingling induced by the experimental current.

Excerpts from Know your enemy: How to make soldiers’ brains better at noticing threats, Economist, July 29, 2017

Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.

Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.