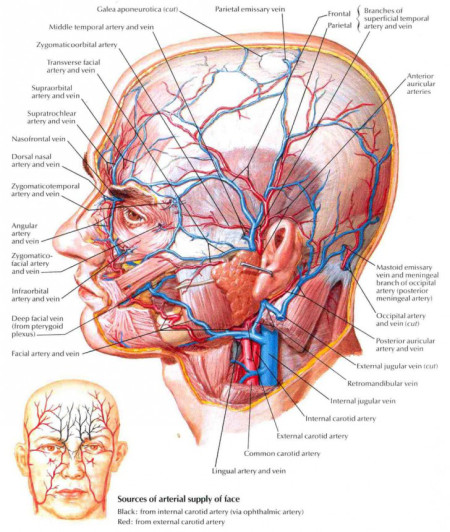

Some brain–computer interfaces (BCI) are capable not only to record conscious thoughts but also the impulses of the preconscious. Most BCIs are connected the brain’s motor cortex, the part of the brain that initiates and controls voluntary movements by sending signals to the body’s muscles. But some people have volunteered to have an extra interface implanted in their posterior parietal cortex, a brain region associated with reasoning, attention and planning…The ability of these devices to access aspects of a person’s innermost life, including preconscious thought, raises the stakes on concerns about how to keep neural data private. It also poses ethical questions about how neurotechnologies might shape people’s thoughts and actions — especially when paired with artificial intelligence…

Consumer neurotech products capture less-sophisticated data than implanted BCIs do. Unlike implanted BCIs, which rely on the firings of specific collections of neurons, most consumer products rely on electroencephalography (EEG). This measures ripples of electrical activity that arise from the averaged firing of huge neuronal populations and are detectable on the scalp. Rather than being created to capture the best recording possible, consumer devices are designed to be stylish (such as in sleek headbands) or unobtrusive (with electrodes hidden inside headphones or headsets for augmented or virtual reality).

Still, EEG can reveal overall brain states, such as alertness, focus, tiredness and anxiety levels. Companies already offer headsets and software that give customers real-time scores relating to these states, with the intention of helping them to improve their sports performance, meditate more effectively or become more productive, for example. AI has helped to turn noisy signals from suboptimal recording systems into reliable data, explains Ramses Alcaide, chief executive of Neurable, a neurotech company in Boston, Massachusetts, that specializes in EEG signal processing and sells a headphone-based headset for this purpose…

With regard to EEG, “There’s a wild west when it comes to the regulatory standards”… A 2024 analysis of the data policies of 30 consumer neurotech companies by the Neurorights Foundation, a non-profit organization in New York City, showed that nearly all had complete control over the data users provided. That means most firms can use the information as they please, including selling it.

The government of Chile and the legislators of four US states have passed laws that give direct recordings of any form of nerve activity protected status. But ethicists fear that such laws are insufficient because they focus on the raw data and not on the inferences that companies can make by combining neural information with parallel streams of digital data. Inferences about a person’s mental health, say, or their political allegiances could still be sold to third parties and used to discriminate against or manipulate a person.

“The data economy, in my view, is already quite privacy-violating and cognitive- liberty-violating,” Ienca says. Adding neural data, he says, “is like giving steroids to the existing data economy”.

Excerpt from Liam Drew, Mind-reading devices can now predict preconscious thoughts: is it time to worry?, Nature, Nov. 19, 2025

Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.

Two millivolts is enough to show that someone has seen something even before he knows he has seen it himself. The two millivolts in question are those associated with P300, a fleeting electrical signal produced by a human brain which has just recognised an object it has been seeking. Crucially, this signal is detectable by electrodes in contact with a person’s scalp before he is consciously aware of having recognised anything.