Colossal Biosciences, the world’s first de-extinction company, announced on October 1, 2024 the formation of The Colossal Foundation…The Foundation is launching with three core programmatic focuses.

Saving today’s at-risk species: Colossal Foundation plans to build a model for integrating cutting-edge biotechnology with conservation efforts to bring back species that have been driven to the brink of extinction. The long term goal is to create a toolkit approach to simplify genetic rescue for conservationists. Initial projects include efforts focused on the Vaquita, Northern White and Sumatran Rhinos, Red Wolf, Northern Quoll, Ivory Billed Woodpecker, and Pink Pigeon.

R&D for Conservation: Colossal will partner to fund and deploy technologies that leverage artificial intelligence…Current projects include the Colossal drone-based anomaly detection system used by Save the Elephants, a vaquita acoustic monitoring program, and an AI-enabled orphaned elephant monitoring system leveraged by Elephant Havens in Botswana.

Ensuring Tomorrow’s Biodiversity: Developing a distributed genetic repository of species (a biobank) which can act as an insurance policy against unforeseen threats to biodiversity and provide a safety net for species facing extinction. The focus will be on those species closest to extinction to ensure their genetic diversity is not lost and the potential to bring them back, should the worst happen, remains.

Vaquitas, a porpoise endemic to the Sea of Cortez/Gulf of California in Baja California, Mexico and the smallest of all living cetaceans, is on the brink of extinction. As of May 2023, only between 10 and 13 vaquitas remain. The loss of the vaquita could be a harbinger of further declines in the Gulf’s marine ecosystems, and the extinction of the vaquita would represent a cultural and symbolic loss. Colossal, in partnership with the Vaquita Monitoring Group and in support of the Mexican government’s La Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) believes that there are low-impact technical solutions that can be used to safely biobank the existing animals while also helping to grow the vaquita population. …

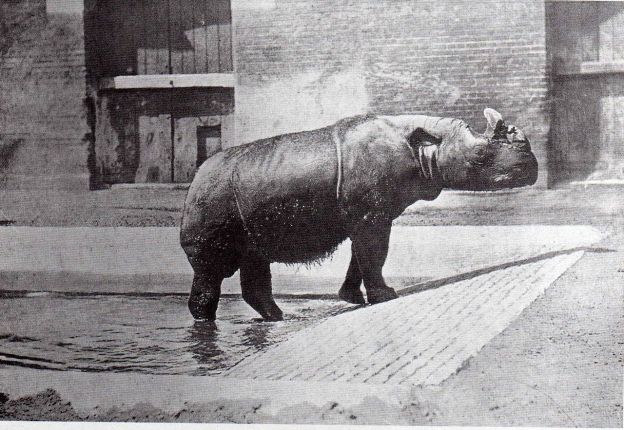

Fewer than 80 Sumatran rhinos survive in tiny fragmented populations across the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo…Colossal Foundation will supporting the Indonesian government’s work to breed Sumatran rhinos under their national conservation breeding program…in collaboration with Global Experts on the advance Assisted Reproductive Technology (a-ART) and Biobank program for the species…

The Colossal BioVault is an initiative, in partnership with Re:wild and others, to collect the primary materials needed to prevent extinction. By collecting tissue samples of the world’s most imperiled species in the Colossal BioVault, the Foundation intends to preserve and store biodiversity.

Excerpts from Colossal Launches The Colossal Foundation, Business Wire, Oct. 1, 2024

SUDAN, the last male northern white rhinoceros on Earth, died in March 2018. He is survived by two females, Najin and her daughter Fatu, who live in a conservancy in Kenya. This pair are thus the only remaining members of the world’s most endangered subspecies of mammal. But all might not yet be lost. Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, in Berlin, in collaboration with Avantea, a biotechnology company in Cremona, Italy, is proposing heroic measures to keep the subspecies alive. In a paper published in Nature, he and his colleagues say that they have created, by in vitro fertilisation (IVF), apparently viable hybrid embryos of northern white rhinos and their cousins from the south. This, they hope, will pave the way for the creation of pure northern-white embryos.

SUDAN, the last male northern white rhinoceros on Earth, died in March 2018. He is survived by two females, Najin and her daughter Fatu, who live in a conservancy in Kenya. This pair are thus the only remaining members of the world’s most endangered subspecies of mammal. But all might not yet be lost. Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, in Berlin, in collaboration with Avantea, a biotechnology company in Cremona, Italy, is proposing heroic measures to keep the subspecies alive. In a paper published in Nature, he and his colleagues say that they have created, by in vitro fertilisation (IVF), apparently viable hybrid embryos of northern white rhinos and their cousins from the south. This, they hope, will pave the way for the creation of pure northern-white embryos.