In November 2023, Michael Morell, a former deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), hinted at a big change in how the agency now operates. “The information that is available commercially would kind of knock your socks off…if we collected it using traditional intelligence methods, it would be top secret-sensitive. And you wouldn’t put it in a database, you’d keep it in a safe.”

In recent years, U.S. intelligence agencies, the military and even local police departments have gained access to enormous amounts of data through shadowy arrangements with brokers and aggregators. Everything from basic biographical information to consumer preferences to precise hour-by-hour movements can be obtained by government agencies without a warrant.

Most of this data is first collected by commercial entities as part of doing business. Companies acquire consumer names and addresses to ship goods and sell services. They acquire consumer preference data from loyalty programs, purchase history or online search queries. They get geolocation data when they build mobile apps or install roadside safety systems in cars. But once consumers agree to share information with a corporation, they have no way to monitor what happens to it after it is collected. Many corporations have relationships with data brokers and sell or trade information about their customers. And governments have come to realize that such corporate data not only offers a rich trove of valuable information but is available for sale in bulk.

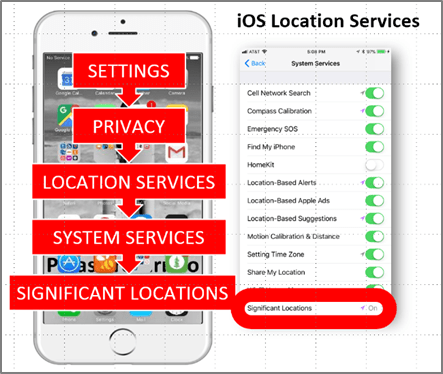

Earlier generations of data brokers vacuumed up information from public records like driver’s licenses and marriage certificates. But today’s internet-enabled consumer technology makes it possible to acquire previously unimaginable kinds of data. Phone apps scan the signal environment around your phone and report back, hourly, about the cell towers, wireless earbuds, Bluetooth speakers and Wi-Fi routers that it encounters….The National Security Agency recently acknowledged buying internet browsing data from private brokers, and several sources have told me about programs allowing the U.S. to buy access to foreign cell phone networks. Those arrangements are cloaked in secrecy, but the data would allow the U.S. to see who hundreds of millions of people around the world are calling.

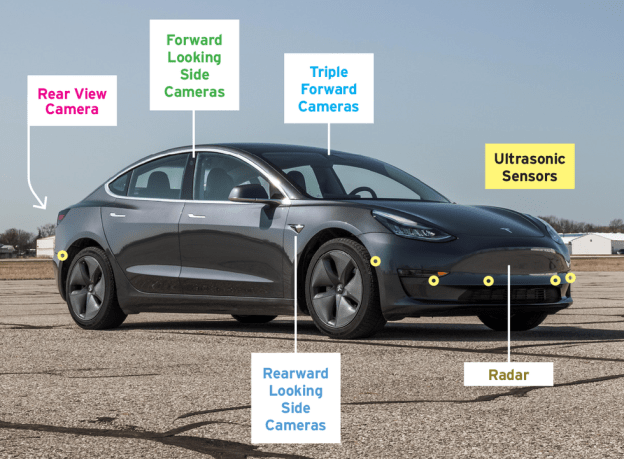

Car companies, roadside assistance services and satellite radio companies also collect geolocation data and sell it to brokers, who then resell it to government entities. Even tires can be a vector for surveillance. That little computer readout on your car that tells you the tire pressure is 42 PSI? It operates through a wireless signal from a tiny sensor, and government agencies and private companies have figured out how to use such signals to track people…

It’s legal for the government to use commercial data in intelligence programs because data brokers have either gotten the consent of consumers to collect their information or have stripped the data of any details that could be traced back to an individual. Much commercially available data doesn’t contain explicit personal information. But the truth is that there are ways to identify people in nearly all anonymized data sets. If you can associate a phone, a computer or a car tire with a daily pattern of behavior or a residential address, it can usually be associated with an individual.

And while consumers have technically consented to the acquisition of their personal data by large corporations, most aren’t aware that their data is also flowing to the government, which disguises its purchases of data by working with contractors. One giant defense contractor, Sierra Nevada, set up a marketing company called nContext which is acquiring huge amounts of advertising data from commercial providers. Big data brokers that have reams of consumer information, like LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters, market products to government entities, as do smaller niche players. Companies like Babel Street, Shadowdragon, Flashpoint and Cobwebs have sprung up to sell insights into what happens on social media or other web forums. Location data brokers like Venntel and Safegraph have provided data on the movement of mobile phones…

A group of U.S. lawmakers is trying to stop the government from buying commercial data without court authorization by inserting a provision to that effect in a spy law, FISA Section 702, that Congress needs to reauthorize by April 19. The proposal would ban U.S. government agencies from buying data on Americans but would allow law-enforcement agencies and the intelligence community to continue buying data on foreigners…But many in the national security establishment think that it makes no sense to ban the government from acquiring data that everyone from the Chinese government to Home Depot can buy on the open market. The data is valuable—in some cases, so valuable that the government won’t even discuss what it’s buying. “Picture getting a suspect’s phone, then in the extraction [of data] being able to see everyplace they’d been in the last 18 months plotted on a map you filter by date ranges,” wrote one Maryland state trooper in an email obtained under public records laws. “The success lies in the secrecy.”

For spies and police officers alike, it is better for people to remain in the dark about what happens to the data generated by their daily activities—because if it were widely known how much data is collected and who buys it, it wouldn’t be such a powerful tool. Criminals might change their behavior. Foreign officials might realize they’re being surveilled. Consumers might be more reluctant to uncritically click “I accept” on the terms of service when downloading free apps. And the American public might finally demand that, after decades of inaction, their lawmakers finally do something about unrestrained data collection.

Excerpts from Byron Tau, US Spy Agencies Know Your Secrets. They Bought Them, WSJ, Mar. 8, 2024

See also Means of Control: How the Hidden Alliance of Tech and Government Is Creating a New American Surveillance State by Byron Tau (published 2024).