Though tensions between Iran and the U.S. have ratcheted up since the Oct. 7, 2024 attacks on Israel by Tehran-backed Hamas, exports from Iran surpassed 1.5 million barrels a day in 2024 starting in February, substantially more than at the start of the Biden presidency. Most of that oil is bought by small Chinese refineries at discounted prices. The U.S. and its allies have been “very, very careful not to go too far and damage the ability of Western economies to function,” when it comes to sanctions, said John Smith, partner at Morrison Foerster and former head of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

U.S. diplomats and energy officials have for decades worked around the globe to keep oil flowing, often involving uncomfortable alliances and accommodations. When the Treasury department hit Moscow with a wave of sanctions on June 12, 2024 over the Ukraine war, it targeted banks but left the country’s oil industry largely untouched. There is frustration among some staffers in the U.S. Treasury Department over the lack of action against oil-trading networks that ferry Russian and Iranian oil, including one that officials are currently investigating, according to U.S. diplomats and some of the energy-industry players briefed by current officials. The network is operated by a little-known trader from Azerbaijan who emerged as the premier middleman for Russia’s Rosneft Oil, The Wall Street Journal reported.

When the Treasury imposed sanctions on Russia’s state tanker owner, Sovcomflot, it also issued licenses exempting all but 14 of the company’s fleet, which data provider Kpler estimates totals 91 ships. Industry players said the exemption licenses were a green light to oil traders to do business with those ships, minimizing the risk that they would be targeted by future sanctions. The National Economic Council, led by Lael Brainard, and others within the administration worried that broader measures would lead to logistical problems in the oil market and boost inflation, said people familiar with the matter. Rising oil output from sanctioned countries is one reason crude prices have fallen from their highs earlier this year, analysts said…

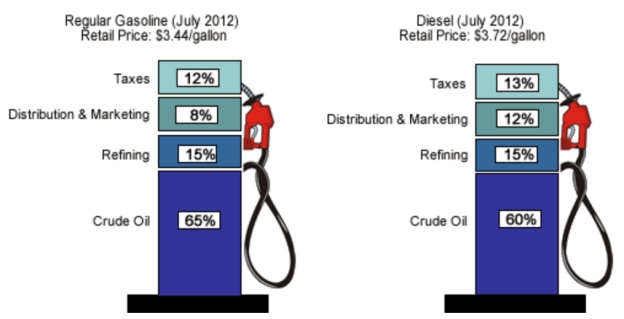

In another example of the collision of foreign and energy policies, earlier this year, Washington asked Ukraine to stop attacking some Russian refineries with drones after the damage rattled global diesel and gasoline markets….

“Nothing terrifies an American president more than a gasoline-pump price spike,” said Bob McNally, president of consulting firm Rapidan Energy Group and former White House policy official under George W. Bush. “They will go to great lengths to prevent this, especially in an election year.”

Excerpts from Anna Hirtenstein et al., Biden Wants to Be Tough With Russia and Iran—but Wants Low Gas Prices Too, WSJ, June 26, 2024