In January 2025, NATO launched the operation, dubbed Baltic Sentry, after a string of undersea cables and pipelines were damaged by ships—many with links to Russia—that had dragged their anchors. “We are functioning as security cameras at sea,” said Kockx, the Belgian commander, whose usual duty is clearing unexploded mines from the busy waterway… New undersea drones are keeping a watchful eye on pipes and cables. NATO surveillance planes from the U.S., France, Germany and occasionally the U.K. take turns scanning the seaway from high above. NATO has also strengthened its military presence on the Baltic…NATO’s goal is to prevent more damage to subsea infrastructure and respond faster if something occurs…

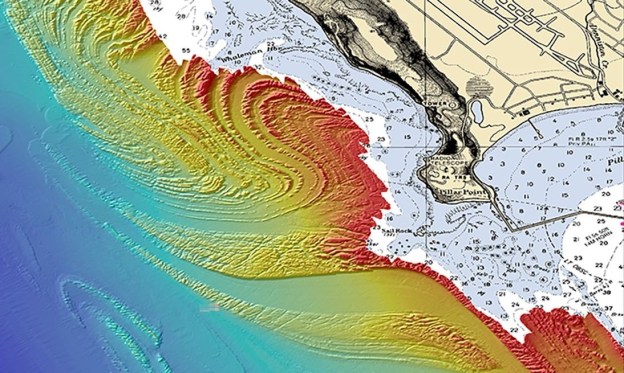

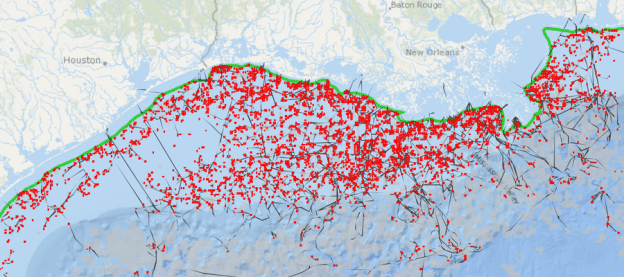

The Baltic, a central theater in two world wars, is littered with wrecks and explosives that still pose danger. Surrounding NATO members are world leaders in finding and disposing of sea mines, officials say….Commercial traffic on the Baltic ranks among the world’s densest, with more than 1,500 ships plying its waves on any day, so policing it all is difficult. Further complicating NATO’s sentry duty initially was a lack of comprehensive information about all the critical infrastructure snaking across the sea’s muddy bottom. Details of pipes and cables have traditionally been kept by national governments or private companies. Nobody had a picture of everything...NATO’s new undersea infrastructure center in 2024 assembled the first unified map of the Baltic’s floor.

Excerpt from Daniel Michaels, How NATO Patrols the Sea for Suspected Russian Sabotage, Mar. 31, 2025