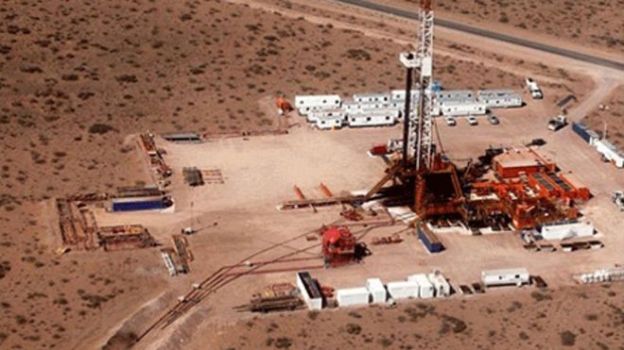

Despite the precipitous fall in global oil prices (from 110 dollars in 2014 to under 50 dollars in 2015), Argentina has continued to follow its strategy of producing unconventional shale oil, although in the short term there could be problems attracting the foreign investment needed to exploit the Vaca Muerta shale deposit, Argentina’s energy trade deficit climbed to almost seven billion dollars in 2014, partly due to the decline in the country’s conventional oil reserves. Eliminating that deficit depends on the development of Vaca Muerta, a major shale oil and gas deposit in the Neuquén basin in southwest Argentina. At least 10 billion dollars a year in investment are needed over the next few years to tap into this source of energy…

According to the state oil company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), Vaca Muerta multiplied Argentina’s oil reserves by a factor of 10 and its gas reserves by a factor of 40, which will enable this country not only to be self-sufficient in energy but also to become a net exporter of oil and gas. YPF has been assigned 12,000 of the 30,000 sq km of the shale oil and gas deposit in the province of Neuquén. The company admits that to exploit the deposit, it will need to partner with transnational corporations capable of providing capital.

It has already done so with the U.S.-based Chevron in the Loma Campana deposit, where it had projected a price of 80 dollars a barrel this year….YPF has also signed agreements for the joint exploitation of shale deposits with Malaysia’s Petronas and Dow Chemical of the United States, while other transnational corporations have announced their intention to invest in Vaca Muerta.

Excerpts from Fabiana Frayssinet, Plunging Oil Prices Won’t Kill Vaca Muerta, PS, Apr. 10, 2015