There are about 30 000 mountains under the sea, the so-called “seamounts.” One of them the Tropic Seamount started as a volcano, 120 million years ago. It lies at the southern tail of a chain that includes submerged peaks as well as the Canary Islands off the coast of Western Sahara. The seamount rises 3 kilometers from the ocean floor and is topped by a plateau 50 kilometers wide, 1 kilometer below the sea surface. Above ground, it would rank among the world’s 100 tallest mountains…. Much of its surface is encrusted with minerals that precipitated out of the seawater over eons, coating the lava at the excruciatingly slow rate of 1 centimeter or less every 1 million years.

That coating has caught the eye of prospectors. Called ferromanganese crust, it can contain high concentrations of cobalt, tellurium, and rare-earth elements used in electronics such as wind turbines, batteries, and solar panels. By one estimate, seamounts in just one chunk of the North Pacific Ocean could hold 50 million tons of cobalt—seven times the worldwide total that’s economical to dig up on land. Such estimates arrive at a time when the International Energy Agency in Vienna is warning of a possible cobalt supply crunch by 2030, caused in part by the growing production of battery-powered cars.

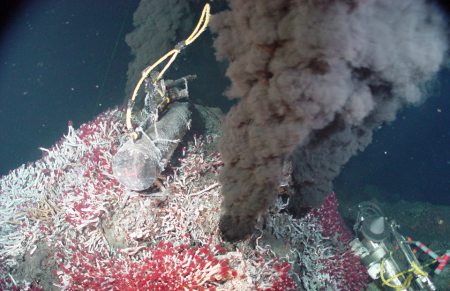

Companies hoping to extract those metals from the seabed are focusing first on abyssal plains. Those flat expanses of the deep ocean floor can be littered with potatolike nodules rich in nickel, copper, and cobalt. They are also looking at hydrothermal vents that spew mineral-laden water, creating thick crusts and fantastical rock chimneys. Seventeen companies have permits to explore for minerals in one abyssal region, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico. And in 2017, Japan became the first nation to conduct large-scale experimental mining of a dead hydrothermal vent off the coast of Okinawa, inside Japan’s national waters. But the crusts on seamounts have particularly high concentrations of sought-after metals, making them a tempting target…

[Scientists are worried] that what they have learned from the the Tropic Seamount puts mining and conservation on a collision course. “The conditions that seem to favor the growth of the crusts,” he says, “also seem to favor the colonization by a lot of corals and sponges.”

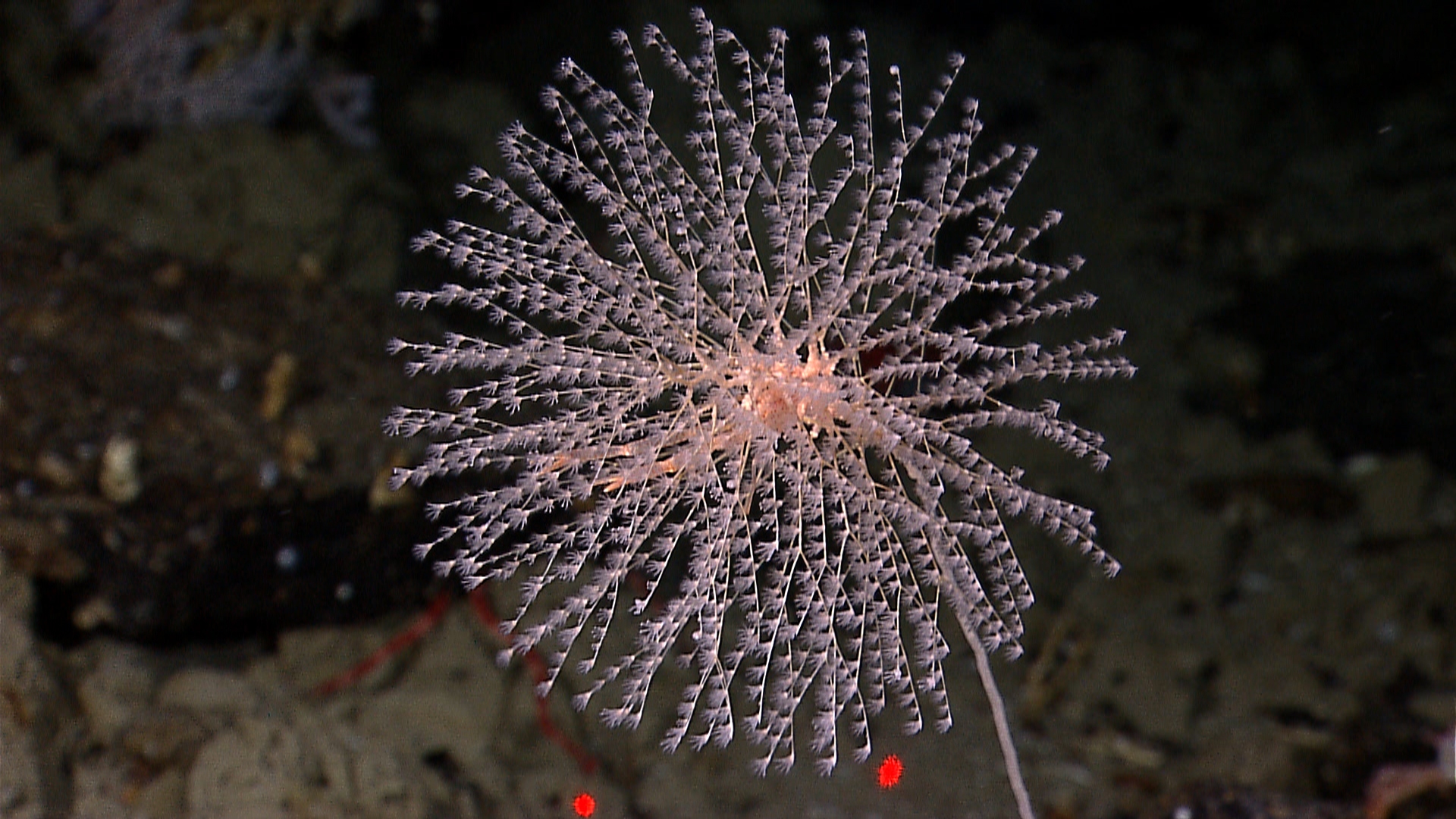

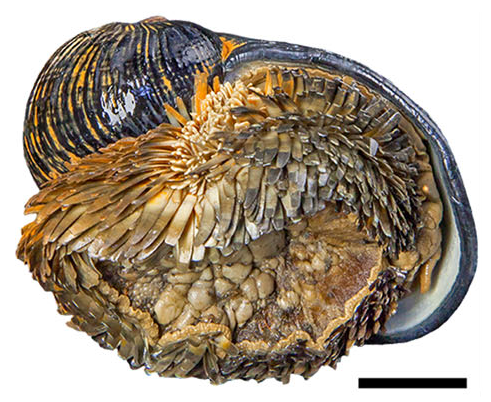

Seamounts cover roughtly the same area as Russia and Europe combined, by one estimate, making them one of the planet’s largest habitats. The peaks have long been known as oases for sea life….Schools of fish—brick-red orange roughy, silvery pelagic armorheads, and goggle-eyed black oreos—often congregate at seamounts, as do sharks and tuna. Some migratory humpback whales appear to use them as navigational markers, spawning grounds, and resting spots. Seabirds gather above them, and myriad corals and sponges cling to their rocky surfaces, creating ample cover for other creatures.

Interest in seamounts is particularly high in countries that either host companies interested in deep-sea mining or are considering allowing mining in their national waters. In 2018, the Chinese research ship Kexue (meaning “science”) spent about 1 month surveying the Magellan Seamounts near the Mariana Trench, which several nations see as a potential source of industrial minerals. Brazilian researchers teamed up with Murton’s MarineE-tech project to examine an area in international waters where the country has a preliminary mining claim. Japanese scientists sent robots to survey seamounts that might be ripe for mining. In late July, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Kingston, a part of the United Nations that governs deep-sea mining in international waters, released 18 years of environmental data gathered by companies pursuing mining claims, including on seamounts….

The design of seamount mining equipment is closely guarded by competing countries and companies. But it could work much like equipment being tested for hydrothermal vents: enormous, remote-controlled machines that resemble bulldozers, equipped with toothed wheels designed to grind the crust into bits that can be carried to the ocean surface for processing.

Although no seamount has been mined yet, scientists point to the damage from deep-sea fishing to underscore why they worry this heavy machinery would do irreparable damage. In the late 1990s, Australian scientists documented devastation from nets dragged across seamounts near Tasmania to catch orange roughy. Hard corals had been wiped out, and the sheer mass of life on the mountains was half that on nearby ones too deep to be fished. Fifteen years after trawling was halted on some New Zealand seamounts, Clark and other researchers found little evidence of recovery.

Excerpts from Warren Cornwall, Sunken Summits, Science, Sept 13, 2019