The government of Tanzania claims that the Maasai, the indigenous people of Tanzania, present a threat to the ecosystem of the Serengeti National Park. The government says the seminomadic cattle farmers are a threat to the savannas and watering holes in an area that sustains the country’s money-spinning safari resorts and hunting reserves and, more recently, a swath of new carbon-credit projects.

To protect these areas, President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s government has outlawed human settlement there and begun evicting some of the more than 110,000 Maasai from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area—the vast zone of grass-, wood- and wetlands adjacent to the Serengeti that the Maasai have used for both herding and tourism for the past 65 years.

The area includes the famous Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest, fully-intact caldera and home of one of Africa’s densest populations of zebras, gazelles and other large mammals…The government argues that the number of Maasai living in Ngorongoro has expanded from just 8,000 in 1959, outpacing Tanzania’s overall population growth. The herders, along with their cattle, are overwhelming the area’s fragile ecosystem, it says. Similar warnings have been issued by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or Unesco, which declared the Ngorongoro Conservation Area a World Heritage site in 1979.

But for the Maasai, the evictions are endangering a centuries-old way of life they say is much closer to nature than the rest of rapidly urbanizing Tanzania. They accuse the government of giving priority to revenue from foreign tourists, investors and conservation groups over the lives and livelihoods of some of its own citizens. ..Experts and activists focused on the rights of indigenous people say the Maasai are the latest group caught in the murky intersection of tourism, biodiversity protection and global climate goals. Similar conservation-related evictions have also targeted indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon and the Nouabalé-Ndoki rainforest in the Republic of Congo.

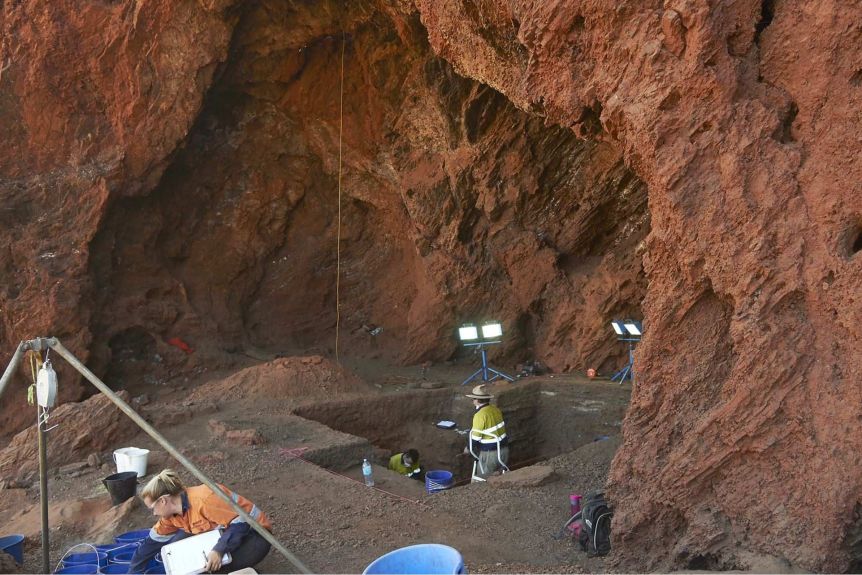

Revenue from tourism jumped 40% to $3.5 billion in 2023, about 17% of Tanzania’s gross domestic product, and according to government projections could reach $6 billion by 2025. The government has already set aside swaths of land around the Ngorongoro Crater previously reserved for the Maasai for the construction of a China-funded geological park, where tourists and researchers can explore fossils, rock paintings and other archaeological artifacts dating as far back as 4 million years ago. To the south of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a local company called Carbon Tanzania is selling carbon credits linked to about 273,000 acres of land that the Maasai have also used for grazing and limited cultivation. The project restricts the cutting down of trees but allows cultivation in some zones…

One of the most violent standoffs between the Maasai and Tanzanian authorities took place in mid-2022 in the grassy plains of Loliondo, about 100 miles west of Serengeti. Heavily armed police and rangers stormed Maasai villages, fired tear gas and live rounds, and bulldozed hundreds of houses as they sought to seize some 37,000 acres of land for a new game reserve. One police officer was killed by an arrow shot by the Maasai, authorities said. Many Maasai were wounded in the clashes, and thousands fled into neighboring Kenya to seek medical treatment. Dozens of others were arrested. After the mayhem in Loliondo, authorities appeared to have opted for a more tactical approach in neighboring Ngorongoro, closing down schools, water sources and hospitals to force residents out of homes, Maasai activists say.

Excerpts from Nicholas Bariyo, The Safaris and Carbon-Credit Projects Threatening the Serengeti’s Maasai, WSJ, Dec. 22, 2024