Mining company BHP has been found liable on November 13, 2025 for a 2015 dam collapse in Brazil,….[Note that this disaster was followed by yet another disaster in 2019 the Brumadinho dam disaster] The dam collapse killed 19 people, polluted the river and destroyed hundreds of homes. The civil lawsuit, representing more than 600,000 people including civilians, local governments and businesses, had been valued at up to £36bn ($48bn).

The dam in Mariana, southeastern Brazil, was owned by Samarco, a joint venture between the mining giants Vale and BHP. The claimants’ lawyers argued successfully that the trial should be held in London because BHP headquarters “were in the UK at the time of the dam collapse”. A separate claim against Samarco’s second parent company, Brazilian mining company Vale, was filed in the Netherlands, with more than 70,000 plaintiffs.

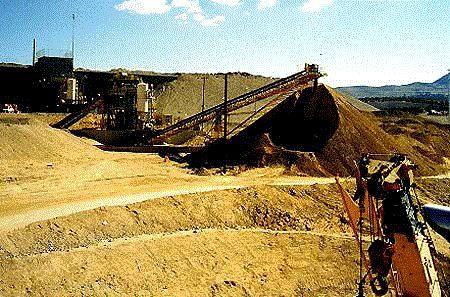

The dam was used to store waste from iron ore mining. When it burst, it unleashed tens of millions of cubic metres of toxic waste and mud. The sludge swept through communities, destroying hundreds of people’s homes and poisoning the river. Judge Finola O’Farrell said in her High Court ruling that continuing to raise the height of the dam when it was not safe to do so was the “direct and immediate cause” of the dam’s collapse, meaning BHP was liable under Brazilian law.

Excerpt from Ione Wells, UK court finds mining firm liable for Brazil’s worst environmental disaster, BBC, Nov. 14, 2025

———-

According to the UN Special Rapporteur who visited Brazil in 2019 and met BHP and Vale on numerous occasions, ” BHP and Vale rushed to create the Renova Foundation to provide the communities [affected by the collapse of the dam] an effective remedy. Unfortunately, the true purpose of the Renova Foundation appeared to be limit liability of BHP and Vale, rather than provide any semblance of an effective remedy…

Furthermore, inadequate information was available about the toxicity of the waste after the Mariana disaster, the companies insisted that it was non-toxic, and rejected calls for precaution. Only three weeks after concerns were raised was information availed. When health impacts in Barra Longa emerged years later, Renova sought to exert ownership of epidemiological and toxicological studies by Ambios to suppress disclosure. Read the full report of the Special Rapporteur here.