The joint announcement by China and Russia in March 20211 on their collaboration to explore the moon has the potential to scramble the geopolitics of space exploration, once again setting up competing programs and goals for the scientific and, potentially, commercial exploitation of the moon. This time, though, the main players will be the United States and China, with Russia as a supporting player.

In recent years, China has made huge advances in space exploration, putting its own astronauts in orbit and sending probes to the moon and to Mars. It has effectively drafted Russia as a partner in missions that it has already planned, outpacing a Russian program that has stalled in recent years. In December 2020, China’s Chang’e-5 mission brought back samples from the moon’s surface, which have gone on display with great fanfare in Beijing. That made China only the third nation, after the United States and the Soviet Union, to accomplish the feat. In the coming months, it is expected to send a lander and rover to the Martian surface, hard on the heels of NASA’s Perseverance, which arrived there in February 2021..

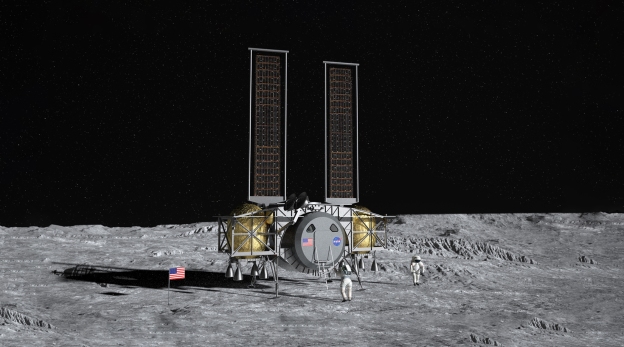

According to a statement by the China National Space Administration, they agreed to “use their accumulated experience in space science research and development and use of space equipment and space technology to jointly formulate a route map for the construction of an international lunar scientific research station.”

After the Soviet Union’s collapse, Russia became an important partner in the development of the International Space Station. With NASA having retired the space shuttle in 2011, Russia’s Soyuz rockets were the only way to get to the International Space Station until SpaceX, a private company founded by the billionaire Elon Musk, sent astronauts into orbit on its own rocket last year. China, by contrast, was never invited to the International Space Station, as American law prohibits NASA from cooperating with Beijing.

China pledged to keep the joint project with Russia “open to all interested countries and international partners,” as the statement put it, but it seemed all but certain to exclude the United States and its allies in space exploration. The United States has its own plans to revisit the moon by 2024 through an international program called Artemis. With Russia by its side, China could now draw in other countries across Asia, Africa and Latin America, establishing parallel programs for lunar development….

Excerpts from China and Russia Agree to Explore the Moon Together, NYT, Mar. 10, 2021