The 2019 World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR2019) assesses the status and trends of the international nuclear industry and analyzes the potential role of nuclear power as an option to combat climate change. Eight interdisciplinary experts from six countries, including four university professors and the Rocky Mountain Institute’s co-founder and chairman emeritus, have contributed to the report.

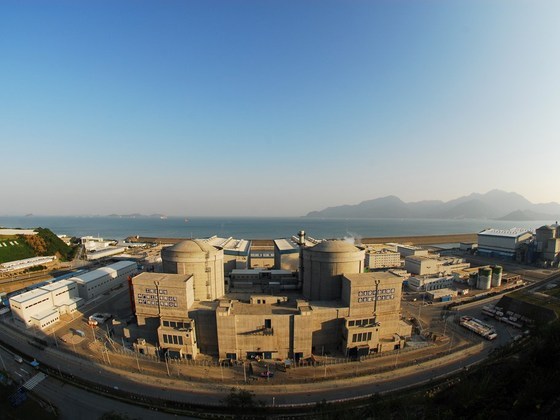

While the number of operating reactors has increased over the past year by four to 417 as of mid-2019, it remains significantly below historic peak of 438 in 2002. Nuclear construction has been shrinking over the past five years with 46 units underway as of mid-2019, compared to 68 reactors in 2013 and 234 in 1979. The number of annual construction starts have fallen from 15 in the pre-Fukushima year (2010) to five in 2018 and, so far, one in 2019. The historic peak was in 1976 with 44 construction starts, more than the total in the past seven years.

WNISR project coordinator and publisher Mycle Schneider stated: “There can be no doubt: the renewal rate of nuclear power plants is too slow to guarantee the survival of the technology. The world is experiencing an undeclared ‘organic’ nuclear phaseout.” Consequently, as of mid-2019, for the first time the average age of the world nuclear reactor fleet exceeds 30 years.

However, renewables continue to outpace nuclear power in virtually all categories. A record 165 gigawatts (GW) of renewables were added to the world’s power grids in 2018; the nuclear operating capacity increased by 9 GW. Globally, wind power output grew by 29% in 2018, solar by 13%, nuclear by 2.4%. Compared to a decade ago, nonhydro renewables generated over 1,900 TWh more power, exceeding coal and natural gas, while nuclear produced less.

What does all this mean for the potential role of nuclear power to combat climate change? WNISR2019 provides a new focus chapter on the question. Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, Professor at the Central European University and Vice-Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group III, notes in her Foreword to WNISR2019 that several IPCC scenarios that reach the 1.5°C temperature target rely heavily on nuclear power and that “these scenarios raise the question whether the nuclear industry will actually be able to deliver the magnitude of new power that is required in these scenarios in a cost-effective and timely manner.”

Over the past decade, levelized cost estimates for utility-scale solar dropped by 88%, wind by 69%, while nuclear increased by 23%. New solar plants can compete with existing coal fired plants in India, wind turbines alone generate more electricity than nuclear reactors in India and China. But new nuclear plants are also much slower to build than all other options, e.g. the nine reactors started up in 2018 took an average of 10.9 years to be completed. In other words, nuclear power is an option that is more expensive and slower to implement than alternatives and therefore is not effective in the effort to battle the climate emergency, rather it is counterproductive, as the funds are then not available for more effective options.

Excerpts from WNISR2019 Assesses Climate Change and the Nuclear Power Option, Sept. 24, 2019

When sub-Saharan Africa comes up in discussions of climate change, it is almost invariably in the context of adapting to the consequences, such as worsening droughts. That makes sense. The region is responsible for just 7.1% of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, despite being home to 14% of its people. Most African countries do not emit much carbon dioxide. Yet there are some notable exceptions.

When sub-Saharan Africa comes up in discussions of climate change, it is almost invariably in the context of adapting to the consequences, such as worsening droughts. That makes sense. The region is responsible for just 7.1% of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, despite being home to 14% of its people. Most African countries do not emit much carbon dioxide. Yet there are some notable exceptions.