Since August 2020, two local governments on the western shore of Hokkaido in Japan have said they will apply to the central government for a survey that could eventually lead to their municipalities hosting a permanent underground repository for high-level radioactive waste. The fact that these two localities made their announcements about a month apart and are situated not far from each other was enough to attract more than the usual media attention, which revealed not only the straitened financial situations of the two areas, but also the muddled official policy regarding waste produced by the country’s nuclear power plants.

The respective populations of the two municipalities reacted differently. The town of Suttsu made its announcement in August 2020, or, at least, its 71-year-old mayor did, apparently without first gaining the understanding of his constituents, who, according to various media, are opposed to the plan…. Meanwhile, the mayor of the village of Kamoenai says he also wants to apply for the study after the local chamber of commerce urged the village assembly to do so in early September 2020. TBS asked residents about the matter and they seemed genuinely in favor of the study because of the village’s fiscal situation. Traditionally, the area gets by on fishing — namely, herring and salmon — which has been in decline for years. A local government whose application for the survey is approved will receive up to ¥2 billion in subsidies from the central government… Kamoenai, already receiving subsidies for nuclear-related matters. The village is 10 kilometers from the Tomari nuclear power plant, where some residents of Kamoenai work. In exchange for allowing the construction of the plant, the village now receives about ¥80 million a year, a sum that accounts for 15 percent of its budget. According to TBS, Kamoenai increasingly relies on that money as time goes by, since its population has declined by more than half over the past 40 years.

Since Japan’s Nuclear Waste Management Organization started soliciting local governments for possible waste storage sites in 2002, a few localities have expressed interest, but only one — the town of Toyo in Kochi Prefecture — has actually applied, and then the residents elected a new mayor who canceled the application. The residents’ concern was understandable: The waste in question can remain radioactive for up to 100,000 years.

The selection process also takes a long time. The first phase survey, which uses existing data to study geological attributes of the given area, requires about two years. If all parties agree to continue, the second phase survey, in which geological samples are taken, takes up to four years. The final survey phase, in which a makeshift underground facility is built, takes around 14 years. And that’s all before construction of the actual repository begins.

Neither Suttsu nor Kamoenai may make it past the first stage. Yugo Ono, an honorary geology professor at Hokkaido University, told the magazine Aera that Suttsu is located relatively close to a convergence of faults that caused a major earthquake in 2018. And Kamoenai is already considered inappropriate for a repository on a map drawn up by the trade ministry in 2017.

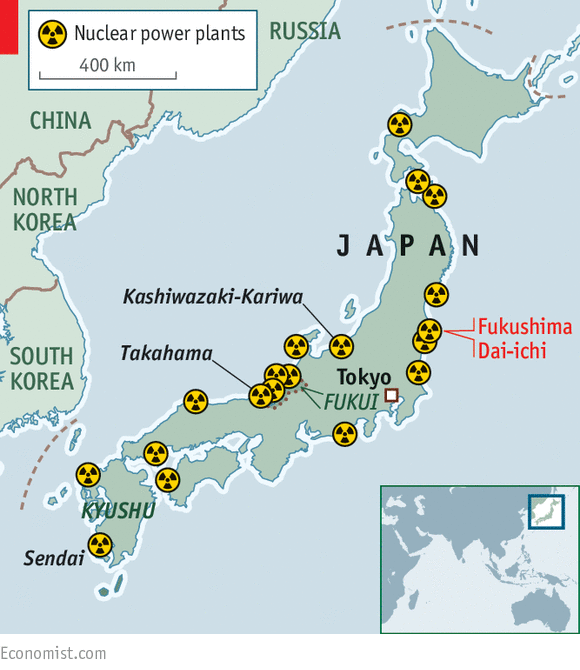

If the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s process for selecting a site sounds arbitrary, it could reflect the government’s general attitude toward future plans for nuclear power, which is still considered national policy, despite the fact that only three reactors nationwide are online.

Japan’s spent fuel is being stored in cooling pools at 17 nuclear plants comprising a storage capacity of 21,400 tons. As of March 2020, 75 percent of that capacity was being used, so there is still some time to find a final resting place for the waste. Some of this spent fuel was supposed to be recycled at the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant in Aomori Prefecture, but, due to numerous setbacks, it doesn’t look as if it’s ever going to open, so the fuel will just become hazardous garbage.

According to some, the individual private nuclear plants should be required to manage their own waste themselves. If they don’t have the capacity, then they should create more. It’s wrong to bury the waste 300 meters underground because many things can happen over the course of future millennia. The waste should be in a safe place on the surface, where it can be readily monitored. However, that would require lots of money virtually forever, something the government would prefer not to think about, much less explain. Instead, they’ve made plans that allow them to kick the can down the road for as long as possible.

Excerpt from PHILIP BRASOR, Hokkaido municipalities gamble on a nuclear future, but at what cost? Japan Times, Oct. 24, 2020