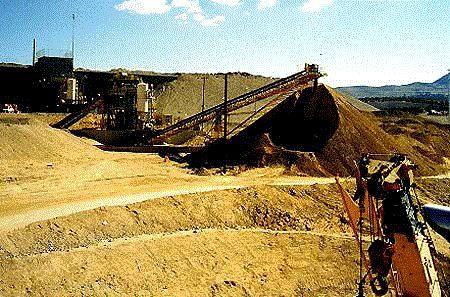

Some 20,000 labourers are working around the clock at Belo Monte on the Xingu river, the biggest hydropower plant under construction anywhere. When complete, its installed capacity, or theoretical maximum output, of 11,233MW will make it the world’s third-largest, behind China’s Three Gorges and Itaipu, on the border between Brazil and Paraguay. Everything about Belo Monte is outsized, from the budget (28.9 billion reais, or $14.4 billion), to the earthworks—a Panama Canal-worth of soil and rock is being excavated—to the controversy surrounding it. In 2008 a public hearing in Altamira, the nearest town, saw a government engineer cut with a machete. In 2010 court orders threatened to stop the auction for the project. The private-sector bidders pulled out a week before. When officials from Norte Energia, the winning consortium of state-controlled firms and pension funds, left the auction room, they were greeted by protesters—and three tonnes of pig muck.

Since then construction has twice been halted briefly by legal challenges. Greens and Amerindians often stage protests. Xingu Vivo (“Living Xingu”), an anti-Belo Monte campaign group, displays notes from supporters all over the world in its Altamira office… But visit the site and Belo Monte now looks both unstoppable and much less damaging to the environment than some of its foes claim…

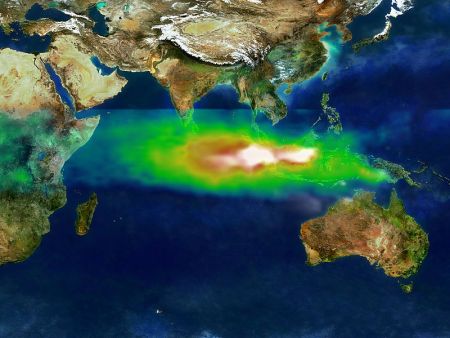

Brazil already generates 80% of its electricity from hydro plants—far more than other countries. But two-thirds of its hydro potential is untapped. The snag is that most of it lies in untouched rivers in the Amazon basin. Of 48 planned dams, 30 are in the rainforest. They include the almost completed Jirau and Santo Antônio on the Madeira river, which will add 6,600MW to installed capacity. But it is Belo Monte, the giant among them, that has become the prime target of anti-dams campaigners.Opponents say that dams only look cheap because the impact on locals is downplayed and the value of other uses of rivers—for fishing, transport and biodiversity—is not counted. They acknowledge that hydropower is low-carbon, but worry that reservoirs in tropical regions can release large amounts of methane, a much more powerful greenhouse gas.

In the 20th century thousands of dams were built around the world. Some were disasters: Brazil’s Balbina dam near Manaus, put up in the 1980s, flooded 2,400 square km (930 square miles) of rainforest for a piffling capacity of 250MW. Its vast, stagnant reservoir makes it a “methane factory”, says Philip Fearnside of the National Institute for Amazonian Research, a government body in Manaus. Proportionate to output, it emits far more greenhouse gases than even the most inefficient coal plant.

But many dams were worth it (though the losers rarely received fair compensation). Itaipu, built in the 1970s by Brazil’s military government, destroyed some of the world’s loveliest waterfalls, flooded 1,350 square km and displaced 10,000 families. But it now supplies 17% of Brazil’s electricity and 73% of Paraguay’s. It is highly efficient, producing more energy than the Three Gorges, despite being smaller.

Of Brazil’s total untapped hydropower potential of around 180,000MW, about 80,000MW lies in protected regions, mostly indigenous territories, for which there are no development plans. The government expects to use most of the remaining 100,000MW by 2030, says Mr Ventura. But it will minimise the social and environmental costs, he insists. The new dams will use “run of river” designs, eschewing large reservoirs and relying on the water’s natural flow to power the turbines. And they will not flood any Indian reserves.,,,

The protesters’ legal challenge to Belo Monte is based on the claim that they have not been properly consulted, something the government denies. The constitution says that before exploiting any resource on Amerindian lands, the government must consult the inhabitants. But it is silent on how this should be done. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has a similar clause in its Convention 169 on indigenous rights, to which Brazil is a signatory. The government says that since no demarcated territories will be flooded, such formal protections do not apply. “We hold consultations about the projects we’re doing not because we have to, but because it is right,” says Mr Ventura. Between 2007 and 2010 there were four public hearings and 12 public consultations about Belo Monte, as well as explanatory workshops and 30 visits to Indian villages.

In 2011, in response to a complaint filed by Indian groups, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights called for a halt to construction pending further consultation. That was “precipitate and unjustified”, said the government, refusing the request. The ILO has asked Brazil’s government for more information on how it intends to fulfil its legal obligations.

The legal uncertainty surrounding Belo Monte is bad for both the Indians and contractors, says Mr Sales—not to mention Brazil as a whole. A draft law detailing how to consult indigenous people is expected by the end of the year. But before Congress legislates, ground is likely to have been broken on most of the new dams….

Belo Monte was given an initial budget of 16 billion reais, which had risen to 19 billion reais by the time of the auction. Norte Energia’s winning bid for Belo Monte offered a price of 77.97 reais/MWh. Since then, its budget has risen by a third. Officials insist that the costs are Norte Energia’s problem. That looks disingenuous. The group is almost wholly state-owned. In November, the national development bank gave Norte Energia a loan of 22.5 billion reais—its largest-ever credit. If Belo Monte turns out to be a white elephant, the bill will fall on the taxpayer.

Dams in the Amazon: the Rights and Wrongs of Belo Monte, Economist, May 4, 2013, at 37