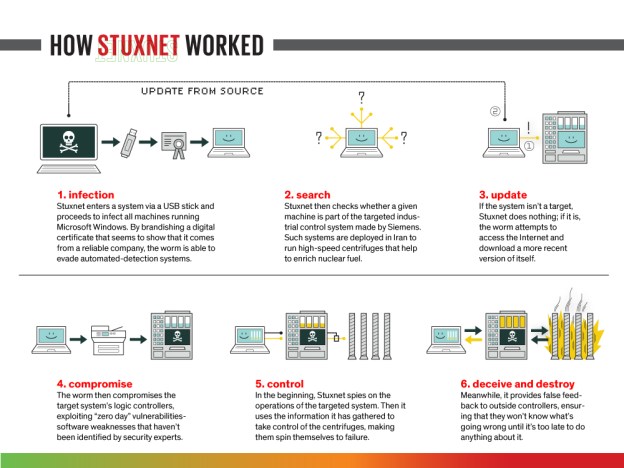

From his first months in office, President Obama secretly ordered increasingly sophisticated attacks on the computer systems that run Iran’s main nuclear enrichment facilities, significantly expanding America’s first sustained use of cyberweapons, according to participants in the program. Mr. Obama decided to accelerate the attacks — begun in the Bush administration and code-named Olympic Games — even after an element of the program accidentally became public in the summer of 2010 because of a programming error that allowed it to escape Iran’s Natanz plant and sent it around the world on the Internet. Computer security experts who began studying the worm, which had been developed by the United States and Israel, gave it a name: Stuxnet. At a tense meeting in the White House Situation Room within days of the worm’s “escape,” Mr. Obama, Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and the director of the Central Intelligence Agency at the time, Leon E. Panetta, considered whether America’s most ambitious attempt to slow the progress of Iran’s nuclear efforts had been fatally compromised. “Should we shut this thing down?” Mr. Obama asked, according to members of the president’s national security team who were in the room. Told it was unclear how much the Iranians knew about the code, and offered evidence that it was still causing havoc, Mr. Obama decided that the cyberattacks should proceed. In the following weeks, the Natanz plant was hit by a newer version of the computer worm, and then another after that. The last of that series of attacks, a few weeks after Stuxnet was detected around the world, temporarily took out nearly 1,000 of the 5,000 centrifuges Iran had spinning at the time to purify uranium.

From his first months in office, President Obama secretly ordered increasingly sophisticated attacks on the computer systems that run Iran’s main nuclear enrichment facilities, significantly expanding America’s first sustained use of cyberweapons, according to participants in the program. Mr. Obama decided to accelerate the attacks — begun in the Bush administration and code-named Olympic Games — even after an element of the program accidentally became public in the summer of 2010 because of a programming error that allowed it to escape Iran’s Natanz plant and sent it around the world on the Internet. Computer security experts who began studying the worm, which had been developed by the United States and Israel, gave it a name: Stuxnet. At a tense meeting in the White House Situation Room within days of the worm’s “escape,” Mr. Obama, Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and the director of the Central Intelligence Agency at the time, Leon E. Panetta, considered whether America’s most ambitious attempt to slow the progress of Iran’s nuclear efforts had been fatally compromised. “Should we shut this thing down?” Mr. Obama asked, according to members of the president’s national security team who were in the room. Told it was unclear how much the Iranians knew about the code, and offered evidence that it was still causing havoc, Mr. Obama decided that the cyberattacks should proceed. In the following weeks, the Natanz plant was hit by a newer version of the computer worm, and then another after that. The last of that series of attacks, a few weeks after Stuxnet was detected around the world, temporarily took out nearly 1,000 of the 5,000 centrifuges Iran had spinning at the time to purify uranium.

This account of the American and Israeli effort to undermine the Iranian nuclear program is based on interviews over the past 18 months with current and former American, European and Israeli officials involved in the program, as well as a range of outside experts. None would allow their names to be used because the effort remains highly classified, and parts of it continue to this day. These officials gave differing assessments of how successful the sabotage program was in slowing Iran’s progress toward developing the ability to build nuclear weapons. Internal Obama administration estimates say the effort was set back by 18 months to two years, but some experts inside and outside the government are more skeptical, noting that Iran’s enrichment levels have steadily recovered, giving the country enough fuel today for five or more weapons, with additional enrichment.

Whether Iran is still trying to design and build a weapon is in dispute. The most recent United States intelligence estimate concludes that Iran suspended major parts of its weaponization effort after 2003, though there is evidence that some remnants of it continue.

Iran initially denied that its enrichment facilities had been hit by Stuxnet, then said it had found the worm and contained it. Last year, the nation announced that it had begun its own military cyberunit, and Brig. Gen. Gholamreza Jalali, the head of Iran’s Passive Defense Organization, said that the Iranian military was prepared “to fight our enemies” in “cyberspace and Internet warfare.” But there has been scant evidence that it has begun to strike back.

The United States government only recently acknowledged developing cyberweapons, and it has never admitted using them. There have been reports of one-time attacks against personal computers used by members of Al Qaeda, and of contemplated attacks against the computers that run air defense systems, including during the NATO-led air attack on Libya last year. But Olympic Games was of an entirely different type and sophistication.

It appears to be the first time the United States has repeatedly used cyberweapons to cripple another country’s infrastructure, achieving, with computer code, what until then could be accomplished only by bombing a country or sending in agents to plant explosives. The code itself is 50 times as big as the typical computer worm, Carey Nachenberg, a vice president of Symantec, one of the many groups that have dissected the code, said at a symposium at Stanford University in April. Those forensic investigations into the inner workings of the code, while picking apart how it worked, came to no conclusions about who was responsible.

A similar process is now under way to figure out the origins of another cyberweapon called Flame that was recently discovered to have attacked the computers of Iranian officials, sweeping up information from those machines. But the computer code appears to be at least five years old, and American officials say that it was not part of Olympic Games. They have declined to say whether the United States was responsible for the Flame attack.

Mr. Obama, according to participants in the many Situation Room meetings on Olympic Games, was acutely aware that with every attack he was pushing the United States into new territory, much as his predecessors had with the first use of atomic weapons in the 1940s, of intercontinental missiles in the 1950s and of drones in the past decade. He repeatedly expressed concerns that any American acknowledgment that it was using cyberweapons — even under the most careful and limited circumstances — could enable other countries, terrorists or hackers to justify their own attacks.

“We discussed the irony, more than once,” one of his aides said. Another said that the administration was resistant to developing a “grand theory for a weapon whose possibilities they were still discovering.” Yet Mr. Obama concluded that when it came to stopping Iran, the United States had no other choice.If Olympic Games failed, he told aides, there would be no time for sanctions and diplomacy with Iran to work. Israel could carry out a conventional military attack, prompting a conflict that could spread throughout the region.

The impetus for Olympic Games dates from 2006, when President George W. Bush saw few good options in dealing with Iran. At the time, America’s European allies were divided about the cost that imposing sanctions on Iran would have on their own economies. Having falsely accused Saddam Hussein of reconstituting his nuclear program in Iraq, Mr. Bush had little credibility in publicly discussing another nation’s nuclear ambitions. The Iranians seemed to sense his vulnerability, and, frustrated by negotiations, they resumed enriching uranium at an underground site at Natanz, one whose existence had been exposed just three years before.

Iran’s president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, took reporters on a tour of the plant and described grand ambitions to install upward of 50,000 centrifuges. For a country with only one nuclear power reactor — whose fuel comes from Russia — to say that it needed fuel for its civilian nuclear program seemed dubious to Bush administration officials. They feared that the fuel could be used in another way besides providing power: to create a stockpile that could later be enriched to bomb-grade material if the Iranians made a political decision to do so. Hawks in the Bush administration like Vice President Dick Cheney urged Mr. Bush to consider a military strike against the Iranian nuclear facilities before they could produce fuel suitable for a weapon. Several times, the administration reviewed military options and concluded that they would only further inflame a region already at war, and would have uncertain results.

For years the C.I.A. had introduced faulty parts and designs into Iran’s systems — even tinkering with imported power supplies so that they would blow up — but the sabotage had had relatively little effect. General James E. Cartwright, who had established a small cyberoperation inside the United States Strategic Command, which is responsible for many of America’s nuclear forces, joined intelligence officials in presenting a radical new idea to Mr. Bush and his national security team. It involved a far more sophisticated cyberweapon than the United States had designed before.

The goal was to gain access to the Natanz plant’s industrial computer controls. That required leaping the electronic moat that cut the Natanz plant off from the Internet — called the air gap, because it physically separates the facility from the outside world. The computer code would invade the specialized computers that command the centrifuges. The first stage in the effort was to develop a bit of computer code called a beacon that could be inserted into the computers, which were made by the German company Siemens and an Iranian manufacturer, to map their operations. The idea was to draw the equivalent of an electrical blueprint of the Natanz plant, to understand how the computers control the giant silvery centrifuges that spin at tremendous speeds. The connections were complex, and unless every circuit was understood, efforts to seize control of the centrifuges could fail.

Eventually the beacon would have to “phone home” — literally send a message back to the headquarters of the National Security Agency that would describe the structure and daily rhythms of the enrichment plant. Expectations for the plan were low; one participant said the goal was simply to “throw a little sand in the gears” and buy some time. Mr. Bush was skeptical, but lacking other options, he authorized the effort. It took months for the beacons to do their work and report home, complete with maps of the electronic directories of the controllers and what amounted to blueprints of how they were connected to the centrifuges deep underground. Then the N.S.A. and a secret Israeli unit respected by American intelligence officials for its cyberskills set to work developing the enormously complex computer worm that would become the attacker from within. The unusually tight collaboration with Israel was driven by two imperatives. Israel’s Unit 8200, a part of its military, had technical expertise that rivaled the N.S.A.’s, and the Israelis had deep intelligence about operations at Natanz that would be vital to making the cyberattack a success. But American officials had another interest, to dissuade the Israelis from carrying out their own pre-emptive strike against the Iranian nuclear facilities. To do that, the Israelis would have to be convinced that the new line of attack was working. The only way to convince them, several officials said in interviews, was to have them deeply involved in every aspect of the program.

Soon the two countries had developed a complex worm that the Americans called “the bug.” But the bug needed to be tested. So, under enormous secrecy, the United States began building replicas of Iran’s P-1 centrifuges, an aging, unreliable design that Iran purchased from Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani nuclear chief who had begun selling fuel-making technology on the black market. Fortunately for the United States, it already owned some P-1s, thanks to the Libyan dictator, Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi. When Colonel Qaddafi gave up his nuclear weapons program in 2003, he turned over the centrifuges he had bought from the Pakistani nuclear ring, and they were placed in storage at a weapons laboratory in Tennessee. The military and intelligence officials overseeing Olympic Games borrowed some for what they termed “destructive testing,” essentially building a virtual replica of Natanz, but spreading the test over several of the Energy Department’s national laboratories to keep even the most trusted nuclear workers from figuring out what was afoot.

Those first small-scale tests were surprisingly successful: the bug invaded the computers, lurking for days or weeks, before sending instructions to speed them up or slow them down so suddenly that their delicate parts, spinning at supersonic speeds, self-destructed. After several false starts, it worked. One day, toward the end of Mr. Bush’s term, the rubble of a centrifuge was spread out on the conference table in the Situation Room, proof of the potential power of a cyberweapon. The worm was declared ready to test against the real target: Iran’s underground enrichment plant.

“Previous cyberattacks had effects limited to other computers,” Michael V. Hayden, the former chief of the C.I.A., said, declining to describe what he knew of these attacks when he was in office. “This is the first attack of a major nature in which a cyberattack was used to effect physical destruction,” rather than just slow another computer, or hack into it to steal data… Getting the worm into Natanz, however, was no easy trick. The United States and Israel would have to rely on engineers, maintenance workers and others — both spies and unwitting accomplices — with physical access to the plant. “That was our holy grail,” one of the architects of the plan said. “It turns out there is always an idiot around who doesn’t think much about the thumb drive in their hand.”

In fact, thumb drives turned out to be critical in spreading the first variants of the computer worm; later, more sophisticated methods were developed to deliver the malicious code. The first attacks were small, and when the centrifuges began spinning out of control in 2008, the Iranians were mystified about the cause, according to intercepts that the United States later picked up. “The thinking was that the Iranians would blame bad parts, or bad engineering, or just incompetence,” one of the architects of the early attack said. The Iranians were confused partly because no two attacks were exactly alike. Moreover, the code would lurk inside the plant for weeks, recording normal operations; when it attacked, it sent signals to the Natanz control room indicating that everything downstairs was operating normally. “This may have been the most brilliant part of the code,” one American official said.

Later, word circulated through the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Vienna-based nuclear watchdog, that the Iranians had grown so distrustful of their own instruments that they had assigned people to sit in the plant and radio back what they saw. “The intent was that the failures should make them feel they were stupid, which is what happened,” the participant in the attacks said. When a few centrifuges failed, the Iranians would close down whole “stands” that linked 164 machines, looking for signs of sabotage in all of them. “They overreacted,” one official said. “We soon discovered they fired people.”

Imagery recovered by nuclear inspectors from cameras at Natanz — which the nuclear agency uses to keep track of what happens between visits — showed the results. There was some evidence of wreckage, but it was clear that the Iranians had also carted away centrifuges that had previously appeared to be working well. But by the time Mr. Bush left office, no wholesale destruction had been accomplished. Meeting with Mr. Obama in the White House days before his inauguration, Mr. Bush urged him to preserve two classified programs, Olympic Games and the drone program in Pakistan. Mr. Obama took Mr. Bush’s advice….

But the good luck did not last. In the summer of 2010, shortly after a new variant of the worm had been sent into Natanz, it became clear that the worm, which was never supposed to leave the Natanz machines, had broken free, like a zoo animal that found the keys to the cage. It fell to Mr. Panetta and two other crucial players in Olympic Games — General Cartwright, the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Michael J. Morell, the deputy director of the C.I.A. — to break the news to Mr. Obama and Mr. Biden.

“I don’t think we have enough information,” Mr. Obama told the group that day, according to the officials. But in the meantime, he ordered that the cyberattacks continue. They were his best hope of disrupting the Iranian nuclear program unless economic sanctions began to bite harder and reduced Iran’s oil revenues.

American cyberattacks are not limited to Iran, but the focus of attention, as one administration official put it, “has been overwhelmingly on one country.” There is no reason to believe that will remain the case for long. Some officials question why the same techniques have not been used more aggressively against North Korea. Others see chances to disrupt Chinese military plans, forces in Syria on the way to suppress the uprising there, and Qaeda operations around the world. “We’ve considered a lot more attacks than we have gone ahead with,” one former intelligence official said….

Mr. Obama has repeatedly told his aides that there are risks to using — and particularly to overusing — the weapon. In fact, no country’s infrastructure is more dependent on computer systems, and thus more vulnerable to attack, than that of the United States. It is only a matter of time, most experts believe, before it becomes the target of the same kind of weapon that the Americans have used, secretly, against Iran.

DAVID E. SANGER,Obama Order Sped Up Wave of Cyberattacks Against Iran, New York Times, June 1, 2012