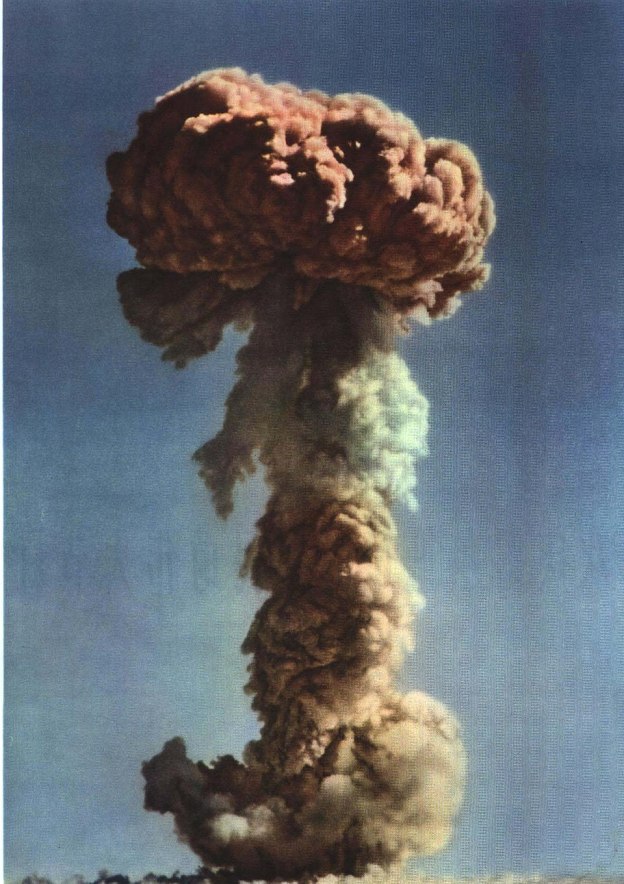

In the afternoon on 22 June 2020, a seismic station in eastern Kazakhstan registered two small earthquakes 12 seconds apart near China’s Lop Nur nuclear test site. Closely spaced jolts can arise from underground explosions followed by a cavity collapse, or simply from earthquakes. U.S. officials in February 2026 asserted the shaking was from a clandestine nuclear detonation—an accusation that could sound the starting gun for a new global arms race…. Low-yield tests would help China refine weapons designs and probe plutonium properties as it expands from a stockpile of about 600 nuclear weapons to what the Pentagon projects will be roughly 1000 by 2030.

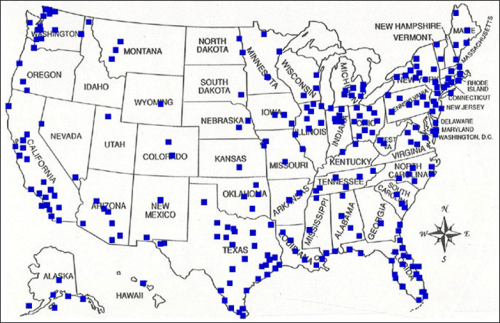

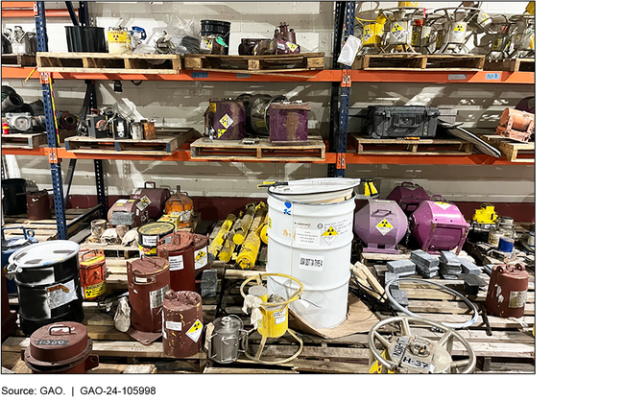

Such tests contravene the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which has not entered into force since the major nuclear powers, such as China and the United States, have not ratified it and Russia rescinded ratification in 2023. Renewed testing would also underscore the limitations of the CTBT and its International Monitoring System (IMS), a global network of instruments that can spot blatant treaty violations but is not equipped to distinguish low-yield tests from earthquakes or nonnuclear blasts.

Incentives for nuclear testing are strong. The U.S. is developing a new submarine-launched warhead, Russia is deploying hypersonic missiles nearly impossible to intercept, and China is ramping up its arsenal. All three powers need to ensure the reliability of new or existing warheads, and they may calculate that insights gleaned from low-yield tests outweigh the risks of adversaries following suit. Heightening concerns is the lapse this month of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which capped U.S. and Russian deployed nuclear warheads at 1550 each.

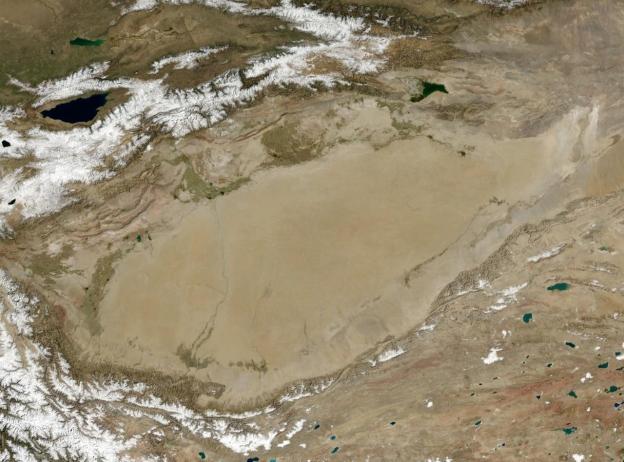

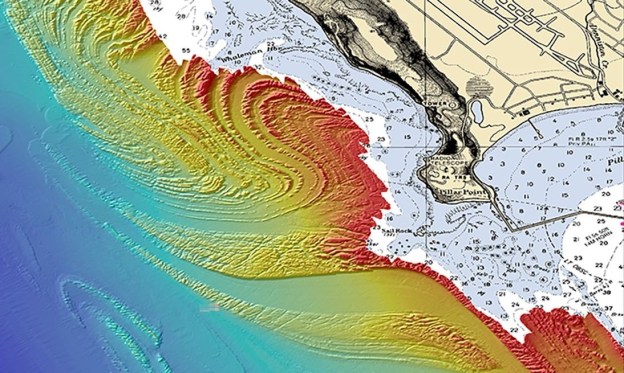

In 2025, satellite images circulated of what appears to be a new laser fusion complex in Sichuan province akin to the U.S. National Ignition Facility, which weapons scientists use to simulate the intense temperatures and pressures of a thermonuclear explosion. Other imagery has spotted the excavation of three tunnels and 30-meter-tall rigs for drilling shafts at Lop Nur. Renny Babiarz, a geospatial analyst with AllSource Analysis, believes two shafts dug in the past few years are “most likely” for yield-producing nuclear tests.

Excerpt from Richard Stone, Allegations of a Chinese nuclear blast may reignite weapons testing, Science, Feb. 24, 20