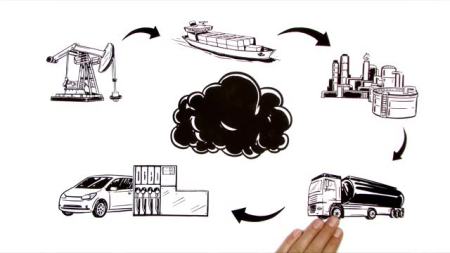

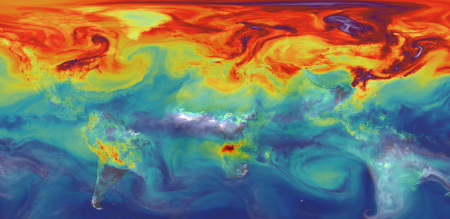

The methane over the Permian Basin emitted by oil companies’ gas venting and flaring is double previous estimates, and represents a leakage rate about 60% higher than the national average from oil and gas fields, according to the research, which was publishe in the journal Science Advances. Methane is the primary component of natural gas. It also is a powerful driver of climate change that is 34 times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere over the span of a century. Eliminating methane pollution is essential to preventing the globe from warming more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit)—the primary target of the Paris climate accord, scientists say.

The researchers used satellite data gathered in 2018 and 2019 to measure and model methane escaping from gas fields in the Permian Basin, which stretches across public and private land in west Texas and southeastern New Mexico. The leaking and flaring of methane had a market value of nearly $250 million in April 2020.

Methane pollution is common in shale oil and gas fields such as those in the Permian Basin because energy companies vent and burn off excess natural gas when there are insufficient pipelines and processing equipment to bring the gas to market. About 30% of U.S. oil production occurs in the Permian Basin, and high levels of methane pollution have been recorded there in the past. Industry groups such as the Texas Methane and Flaring Coalition have criticized previous methane emission research. The coalition has repeatedly said (Environmental Defense Fund) EDF’s earlier Permian pollution data were exaggerated and flawed.

The Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry in Texas, allows companies to flare and vent their excess gas. The commission didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The use of satellites to measure methane is a different approach than the methods used by federal agencies, including the EPA, which base their estimates on expected leakage rates at oil and gas production equipment on the ground. A “top-down” approach to measuring methane using aircraft or satellite data almost always reveals higher levels of methane emissions than the EPA’s “bottom-up” approach.

Excerpts from Permian Oil Fields Leak Enough Methane for 7 Million Homes, Bloomberg Law, Apr. 22, 2020,

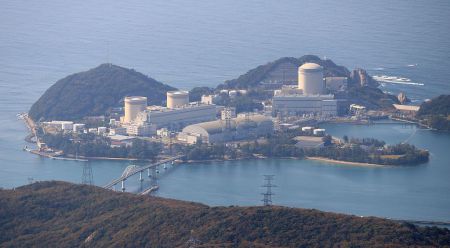

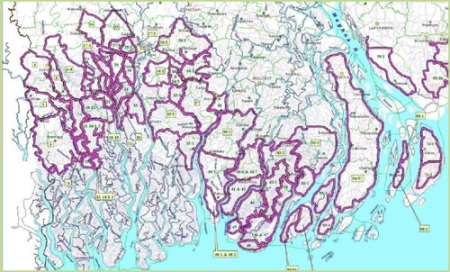

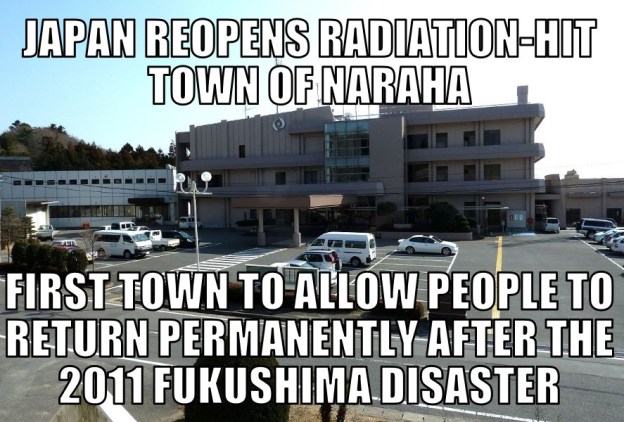

Radioactive cesium from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant continued to flow into Tokyo Bay for five years after the disaster unfolded in March 2011, according to a researcher. Hideo Yamazaki, a former professor of environmental analysis at Kindai University, led the study on hazardous materials that spewed from the nuclear plant after it was hit by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.

Radioactive cesium from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant continued to flow into Tokyo Bay for five years after the disaster unfolded in March 2011, according to a researcher. Hideo Yamazaki, a former professor of environmental analysis at Kindai University, led the study on hazardous materials that spewed from the nuclear plant after it was hit by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.

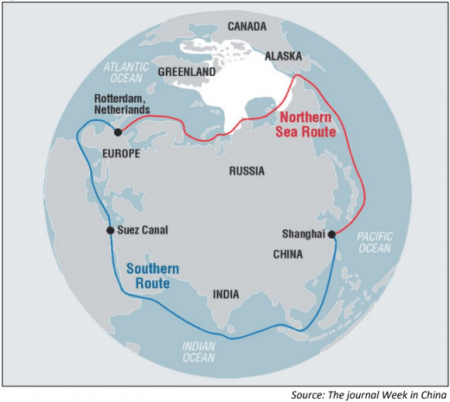

Mr Xi has been showing a growing interest in Arctic countries. In 2014 he revealed in a speech that China itself wanted to become a “polar great power”..,,In January 2018 the Chinese government published its

Mr Xi has been showing a growing interest in Arctic countries. In 2014 he revealed in a speech that China itself wanted to become a “polar great power”..,,In January 2018 the Chinese government published its

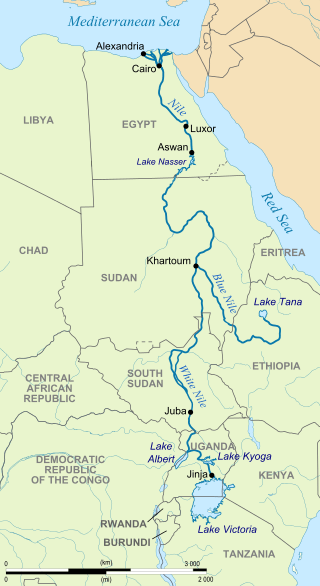

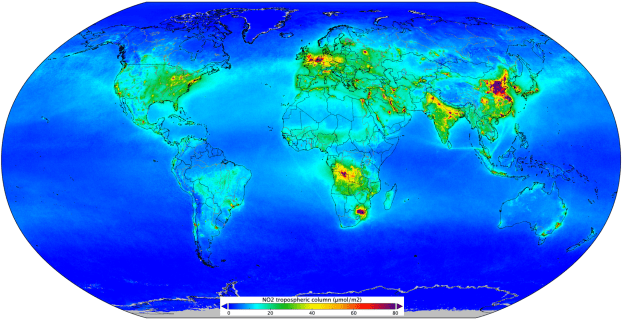

When sub-Saharan Africa comes up in discussions of climate change, it is almost invariably in the context of adapting to the consequences, such as worsening droughts. That makes sense. The region is responsible for just 7.1% of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, despite being home to 14% of its people. Most African countries do not emit much carbon dioxide. Yet there are some notable exceptions.

When sub-Saharan Africa comes up in discussions of climate change, it is almost invariably in the context of adapting to the consequences, such as worsening droughts. That makes sense. The region is responsible for just 7.1% of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, despite being home to 14% of its people. Most African countries do not emit much carbon dioxide. Yet there are some notable exceptions.

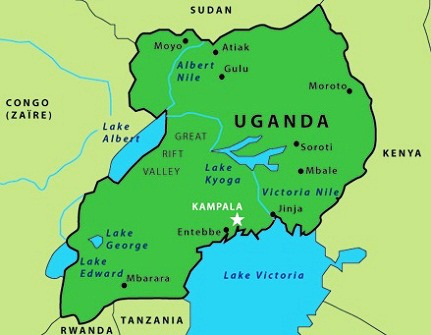

Mukono- Residents of Kitoba village in Mukono District have opposed plans by the Uganda Atomic Energy Council (AEC) to construct a nuclear and atomic waste site in the area. The residents fear the dump for non-functional atomic equipment, including X-rays and cancer machines, will compromise their safety. Already, the residents at Canaan Sites are suspicious of a container that has been standing on the 11.5 acres of land acquired by the AEC in 2011.

Mukono- Residents of Kitoba village in Mukono District have opposed plans by the Uganda Atomic Energy Council (AEC) to construct a nuclear and atomic waste site in the area. The residents fear the dump for non-functional atomic equipment, including X-rays and cancer machines, will compromise their safety. Already, the residents at Canaan Sites are suspicious of a container that has been standing on the 11.5 acres of land acquired by the AEC in 2011.

Nigeria has long ignited interest from oil firms, but it can be a dangerously combustible environment when it comes to the risk of corruption. Two firms caught up in scandals are Royal Dutch Shell and Eni, Italy’s state-backed energy group.

Nigeria has long ignited interest from oil firms, but it can be a dangerously combustible environment when it comes to the risk of corruption. Two firms caught up in scandals are Royal Dutch Shell and Eni, Italy’s state-backed energy group.

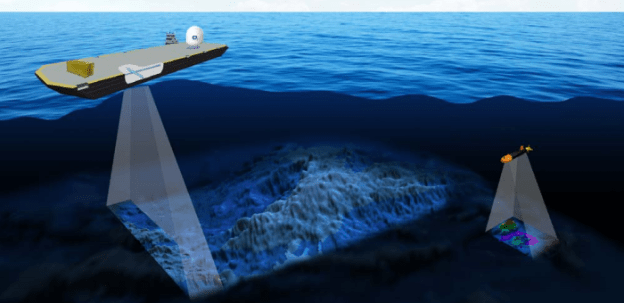

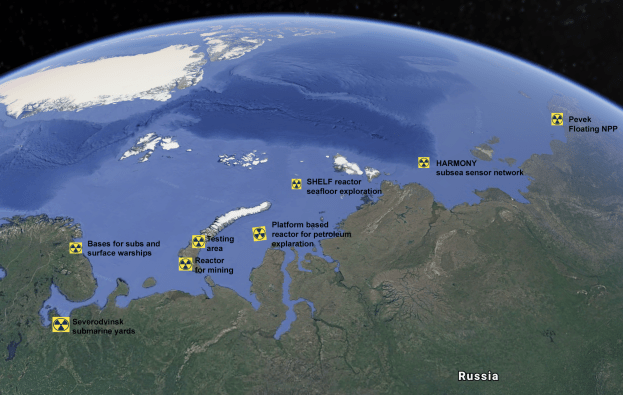

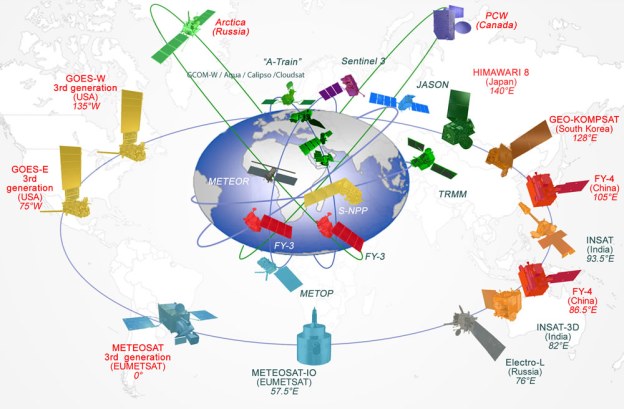

China on January 25, 2018 outlined its ambitions to extend President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative to the Arctic by developing shipping lanes opened up by global warming. Releasing its first official Arctic policy white paper, China said it would encourage enterprises to build infrastructure and conduct commercial trial voyages, paving the way for Arctic shipping routes that would form a “Polar Silk Road”…China, despite being a non-Arctic state, is increasingly active in the polar region and became an observer member of the Arctic Council in 2013.

China on January 25, 2018 outlined its ambitions to extend President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative to the Arctic by developing shipping lanes opened up by global warming. Releasing its first official Arctic policy white paper, China said it would encourage enterprises to build infrastructure and conduct commercial trial voyages, paving the way for Arctic shipping routes that would form a “Polar Silk Road”…China, despite being a non-Arctic state, is increasingly active in the polar region and became an observer member of the Arctic Council in 2013.

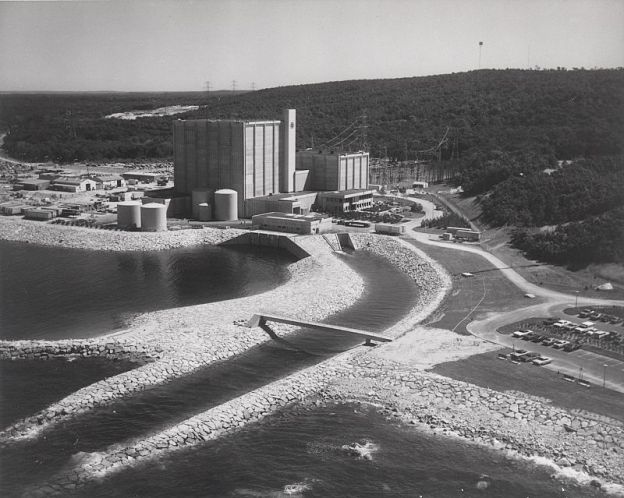

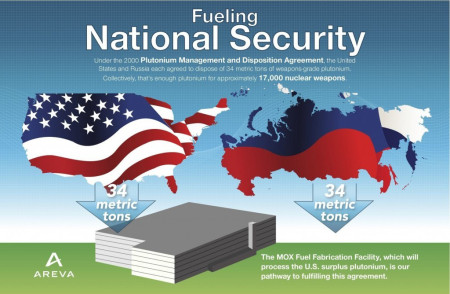

South Carolina is suing the U.S. government to recover $100 million in fines it says the Department of Energy owes the state for failing to remove one metric ton of plutonium stored there. The lawsuit was filed on August 7, 2017.

South Carolina is suing the U.S. government to recover $100 million in fines it says the Department of Energy owes the state for failing to remove one metric ton of plutonium stored there. The lawsuit was filed on August 7, 2017.

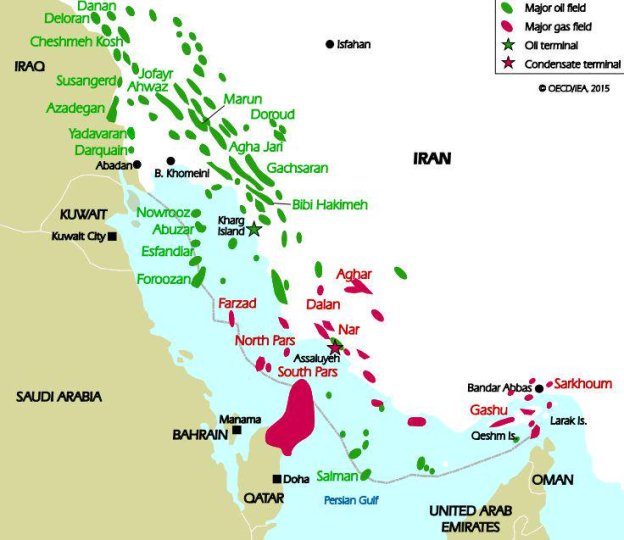

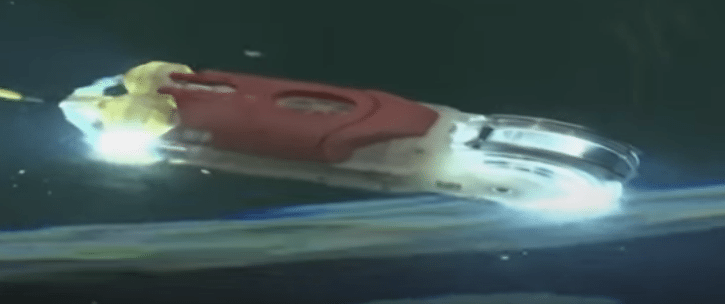

One day in March 2017, he Rioja Knutsen tanker, filled with liquefied natural gas, was traveling from the U.S. to Portugal. Suddenly, Mexico’s power company lobbed in a higher bid for its cargo. At the Bahamas, the ship abruptly made a starboard turn and headed south. How natural gas is bought and sold in the world’s scattered regional markets for the fuel is changing rapidly. Ships such as the Rioja Knutsen are stitching those regions together and a single global market is emerging. This is already how nearly every other hydrocarbon, from crude oil to obscure petrochemicals, is sold. As gas joins the club, the effects will ripple through energy prices, company profits, the environment and geopolitics.

One day in March 2017, he Rioja Knutsen tanker, filled with liquefied natural gas, was traveling from the U.S. to Portugal. Suddenly, Mexico’s power company lobbed in a higher bid for its cargo. At the Bahamas, the ship abruptly made a starboard turn and headed south. How natural gas is bought and sold in the world’s scattered regional markets for the fuel is changing rapidly. Ships such as the Rioja Knutsen are stitching those regions together and a single global market is emerging. This is already how nearly every other hydrocarbon, from crude oil to obscure petrochemicals, is sold. As gas joins the club, the effects will ripple through energy prices, company profits, the environment and geopolitics.

Russia’s sale of one-fifth of its state-owned oil company to Qatar and commodities giant Glencore PLC last year had an unusual provision: Moscow and Doha agreed Russia would buy a stake back, people familiar with the matter said. Russian President Vladimir Putin hailed the $11.5 billion sale of the Rosneft stake in December 2016 as a sign of investor confidence in his country. But the people with knowledge of the deal say it functioned as an emergency loan to help Moscow through a budget squeeze.

Russia’s sale of one-fifth of its state-owned oil company to Qatar and commodities giant Glencore PLC last year had an unusual provision: Moscow and Doha agreed Russia would buy a stake back, people familiar with the matter said. Russian President Vladimir Putin hailed the $11.5 billion sale of the Rosneft stake in December 2016 as a sign of investor confidence in his country. But the people with knowledge of the deal say it functioned as an emergency loan to help Moscow through a budget squeeze.